The Yellow Dog at the Crossroads

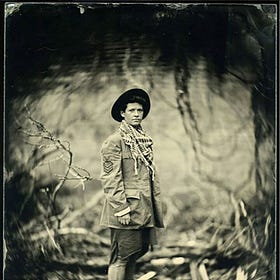

Artist Church Goin Mule tells the tale of a beloved Delta dog, reincarnated.

Sometimes the world seems to conspire,

It used to be that I would drive into the Mississippi Delta and it’d be through a terrifying thunderstorm or in a hard fog, and I’d have to earn my entry. And it used to be I’d find ghosts in old grain bins, like that one time Robert Johnson was singing in the one behind the Shack Up Inn, right in the red of sunset, dazzling, poison ivy and dust and I believe, I believe my time ain’t long,

Sometimes I’d find things I’d interpret as messages. Once walking in the old cypress alongside the Sunflower River, a giant bleached turtle shell said, you’re safe here, welcome home, come on in my kitchen. Like walking the railroad tracks in town and a mean coyote skull meant there’s still more to find, keep looking. Like watching two fox run across the street past the vets down to the river, slick, saying don’t forget to enjoy yourself, it doesn’t all have to be so serious.

And after I moved to the Delta I still kept up with my ghosts, or tried to. Me and my dog Wilbur would go out walking or me and the horse would go out riding the turn rows, and you can sing and dream up into the impossible Delta sky, it has enough room to accept it. Once, bees swarming above us. Once, Wilbur fearlessly chasing a coyote across the field. Once the horse brave enough for the both of us.

Still, after awhile of living somewhere, it gets hard to see the crooked crosses of telephone poles on the highway, or to listen to all of the blues music you’ve been listening to for twenty years. I found myself way out in the country in a new real-old place and could almost see again. It was hard not to take what happened here as a sign to wake up, remember, keep looking.

I’d been knowing Gerald for about a year by this point, we lived together, me and my dog Wilbur and cat Wompus and the chickens. Him and his collection of feral cats and his fifteen year old lab mix, Sandy. Sandy didn’t care about me in the least, and was mostly indifferent to the animals I brought with me, too. Wilbur was respectful and kept his distance. Sandy had earned her place in the land, and took her job of following Gerald to his painting studio every day very seriously. She’d lay out on the wooden floor or concrete while he worked, and if she went out to the yard to lay in the sun, you could be sure she’d come looking for him after she woke up from her nap.

She had showed up as a puppy on the road, a little tannish thing, and her legend grew from there. At fifteen, her face was white with age and she had the appearance of a well-loved teddy bear. Sleeping under the house with the feral cats for much of her life, she was also pretty tough. One of my favorite stories involves her catching a catfish out of the bayou behind the house. She’d go swimming in the pond and walking long miles and would sometimes wander off just to make sure we were paying attention to her. She always rode to town and she taught Wilbur to bark to be let out and bark to be let back in.

One fall we built a ramp on the back steps and mixed paint with sand to give her some grip on it. Her back legs would sometimes give out on her, but she remained determined in all things. Once in the ice storm of 2024, she followed us down the road and across fields with a smile on her face. She still danced for treats, still went to work every day.

Late spring came, Juke Joint Festival passed, and Sandy got poorly on a Saturday. Too late to carry her to the vet, we hoped it would pass. She laid on her bed and hoped it would pass, too, neglecting even her studio supervisory duty. Monday she went to the vet, came home with an infection diagnosis of some kind. That day she went out in the yard just to gaze out into the horizon, I guess, and the three cats came to her. Tuesday, she woke up and went out to the studio all day with her artist, came in and laid on her bed. We had a friend over for supper and she began this coughing barking situation, the friend remarking about her enthusiastic rabbit chasing dream. Me and Gerald exchanged sideways glances, and once supper was over we discovered her spirit seemed to have already left her body, though her body carried on. I had never seen it happen that way, a dog dying a natural death over the course of an hour. We stayed with her, told her she could leave, knowing that the part that mattered had already left. Just past midnight it seemed her wholeness had finally departed. Gerald said, “If it works how it’s supposed to, she’ll be born as a happy puppy somewhere soon.” We covered her up and went to sleep.

The next morning we dug her grave out on the little slope near the pond and wrapped her in one of her falling apart blankets. There was peace that she had lived so long and had health through it all. You couldn’t ask for anything more. She didn’t have to go on a cold table with scared eyes.

Still, magic persists on the land, but if the magic gets hard to find, it helps sometimes to turn to history and myth. A good story can shape a place and bring people in search of it. If you quit paying attention you’ll miss everything.

The story goes that W.C. Handy “discovered” the blues and he did it on a bench in Tutwiler, Mississippi. He was waiting for a train, and saw a man he described as being in rags, playing slide guitar with a knife. “It was the weirdest music I had ever heard,” and the man was singing about “where the Southern cross the Dog.” The interpretation of this line indicates he was singing about the Southern Railroad and the Yellow Dog, or Yazoo-Delta line. Some people write that the Yellow Dog only referred to a dog that was forever chasing the trains through town in Moorhead. Two men are sometimes referred to as either the father or grandfather of the blues and they pick the lyric up—W.C. Handy’s version of the song is colorful and of the time, and Charley Patton’s is a steady rolling-like-a-log blues, I’m goin where the Southern Cross the Dog, some people say the Green River blues ain’t bad, then it must not’ve been the Green River blues I had,

The story goes that Robert Johnson sold his soul at the Crossroads, and there are a few places that claim they’re the “real” crossroads. They’ll get in big nasty Facebook fights about it. The thing is, it could be any place where two roads meet. The main thing is magic accumulates where there is so much activity of cars or traffic of any kind. In Haitian Voudou, which naturally has its roots in Africa, there is a Loa (much like a Saint as opposed to a God, who’ll intercede for you) named Papa Legba, Loa of the Crossroads. He will open doors and paths for you. But the trick is, where I live, Robert Johnson really lived on this road. He lived up a little ways with his wife. She went away to Robinsonville (near Tunica) while she was pregnant, to be with her mother when the time came, following the tradition of the time. She died along with the child, and Robert Johnson left town. It is easy to say his new sound came from the supreme heartbreak and grief of such a loss, or he really learned how to play better down in Hazlehurst (some say other places, some say Memphis), or he really sold his soul to the Devil and became impeccable over night. The death of loved ones makes up a crossroad of its own.

And so maybe when a yellow dog showed up at the crossroads six months after Sandy’s death, I shouldn’t have been surprised. I forgot to look for the magic; it had to do everything to appear to me.

Sometimes the world seems to conspire,

Gerald was on the porch of his new studio agonizing over his most recent painting, like usual. He looked up and saw this little yellow tannish puppy dog sitting at the crossroads with her ears up, “Like, well, I guess I need to make a decision on which way I’ll go.” And he called to her, and she came to him. They met me walking home and from a distance I couldn’t really believe it. The resemblance is uncanny, a lab-shepherd looking creature who demands treats and “smells just like the old Sandy did, like toast.” At first we hoped she’d be an outside dog but we also knew that we were kidding ourselves. She was housebroken almost instantly, and we carried her to the vet to discover that she was six months old. It took her a little while to get back to us, but she was indeed reborn a happy puppy somewhere, just like she was supposed to. We named her Sandii at the suggestion of my father, “You know, like for Sandy Two.”

What magic and history will be revealed here next in the Mississippi Delta waits to be seen, only if I can remember to see the spark in everything. The land takes care of those who keep their feet on it.

As a post-script, I’d like to add that living in the country, dropped off dogs and cats are inevitable. Most of this is due to spaying and neutering being unaffordable for many. Shelters everywhere are at max capacity again—including my local shelter—C.A.R.E.S Clarksdale. I hope you’ll make a donation to your local shelter (or ours) in the name of your beloved and lucky pets.

Church Goin is a southern artist who was born and raised across the South. Her kinfolk came from the mountains, and she keeps her studio in the Mississippi Delta today.

Read more by Church Goin Mule:

Mississippi Transplant: Church Goin Mule

"Home is an awful lot like Love, or God, or Delta. It has its own complex history and Latin names and meaning, but home is how someone says a word, home is a feeling, I wouldn’t define it, in the same way that I believe to my soul Mississippi Is Home."

This is such a good read! My heart was broken & then was healed. 💜

A spiritual gift in SO many ways