Mississippi Transplant: Chris Norment

"Ten years ago, if someone had suggested that I’d move to Mississippi and buy a home here, I would have shaken my head in disbelief. Yet here I am, and I’m happy."

What does it mean to call Mississippi home? Why do people choose to leave or live in this weird, wonderful, and sometimes infuriating place? Chris Norment has written before about his experience grappling with Mississippi’s history and politics and adapting to its hot summers as a recent transplant to the state; today he takes the full Rooted questionnaire. Born and raised in California, Chris has lived and worked all over the country. Most recently, he was professor of environmental science and ecology at the State University of New York - Brockport. As a writer and a scientist, Chris’s understanding of natural world lends him a unique perspective when it comes to making a home in Mississippi. “Visiting beautiful places such as the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge, running at LeFleur’s Bluff, learning to love the deafening thrum of cicadas on a summer evening, listening to a Carolina Wren’s morning song, or finding a swamp rose-mallow blooming at the edge of Mayes Lake: these things, and many more, have helped me feel settled.” Read on to learn how Chris has developed a thriving and eclectic community here in Mississippi.

Where are you from?

I guess that I would have to answer, “From all over.” I was born in Los Angeles, California, and spent most of my youth in the San Francisco Bay Area. I left California for good when I was eighteen and since then I’ve lived in Arizona, Oregon, Nevada, Canada, Washington, Connecticut, and Kansas. Most recently I was a resident of New York State, where I lived from 1993 until 2023.

When did you move to Mississippi and why did you move here?

I began visiting Mississippi in 2018 and moved here permanently in 2023, after retiring from my job in university teaching and research. (I was a vertebrate ecologist.) I made the move because my partner has a job here that she loves—she’s a biologist with the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service—and we were tired of a long-distance relationship.

What does “home” mean to you? How does Mississippi fit into that definition?

For me, “home” has several different meanings. First, there’s what I think of as my “spiritual home”—the place (or places) where I feel most connected to the world, through what I think of as “valence”: the capacity of one thing to positively react with something else. For me, my spiritual home will always be in the open and harsh environments of the American West: the desert, mountains, and high plains, all beyond the hundredth meridian. The philosopher (Bruce Springsteen) once said that “We all carry a landscape within us,” and the landscapes of the American West react with my internal landscape in a powerful and fundamental way. But I also have my “physical home,” which is the place where I have come to rest and feel settled and comfortable. That physical place is—quite surprisingly for me—in Jackson, Mississippi.

What do you miss most about the place where you’re from?

Before moving to Mississippi, I lived for thirty years in a small college town in western New York State. I miss my friends and colleagues there and being able to step outside at noon on a mid-August day and not feel as though I’ve just been hit by a sledgehammer of heat and humidity. I also miss long runs along the path that parallels the Erie Canal, and living near a funky, five-screen movie theater that shows independent and foreign films. Finally, I miss living in a state in which its residents do not vote as though a low tax rate—especially for those who are better off—is the greatest societal good, and that the poor don’t “really” deserve benefits like adequate healthcare and childcare. It’s almost as if some Mississippi politicians are proud that the state ranks close to last in things that are harmful (infant mortality rate, poverty rate, per capita expenditures on K-12 public education, etc.). Cue Tate Reeves, for example.

The philosopher (Bruce Springsteen) once said that “We all carry a landscape within us,” and the landscapes of the American West react with my internal landscape in a powerful and fundamental way. But I also have my “physical home,” which is the place where I have come to rest and feel settled and comfortable. That physical place is—quite surprisingly for me—in Jackson, Mississippi.

How have you cultivated community in Mississippi? Who are the people who have made you feel rooted here?

By finding people who share common interests and values, such as the Zen in Mississippi sangha (Shorinji Zen Association), the Mississippi Humanities Council (I love their reading room events), the Mississippi Film Society, the Rooted community, the Mississippi Trail and Ultra Society (MUTS), the Mississippi Museum of Art, folks at my gym (at St. Dominic’s), and the Mississippi Center for Justice.

I’ve also found a large, diverse community in our neighborhood, where people with divergent political views can still socialize, be friendly, and look out for each other. One place that nurtured my sense of community was Fenian’s Pub—but alas, that closed last September. Some individuals who’ve made me feel rooted here include (first and foremost) my partner, Eli Polzer; Tony Bland, founder of the Zen in Mississippi community and our teacher; good friends on Seneca Street in Fondren; and folks who help nourish the literary scene in Jackson, including Lauren Rhoades and (although he doesn’t know me) John Evans, owner of Lemuria Books. It’s wonderful to have such a good independent bookstore in Jackson!

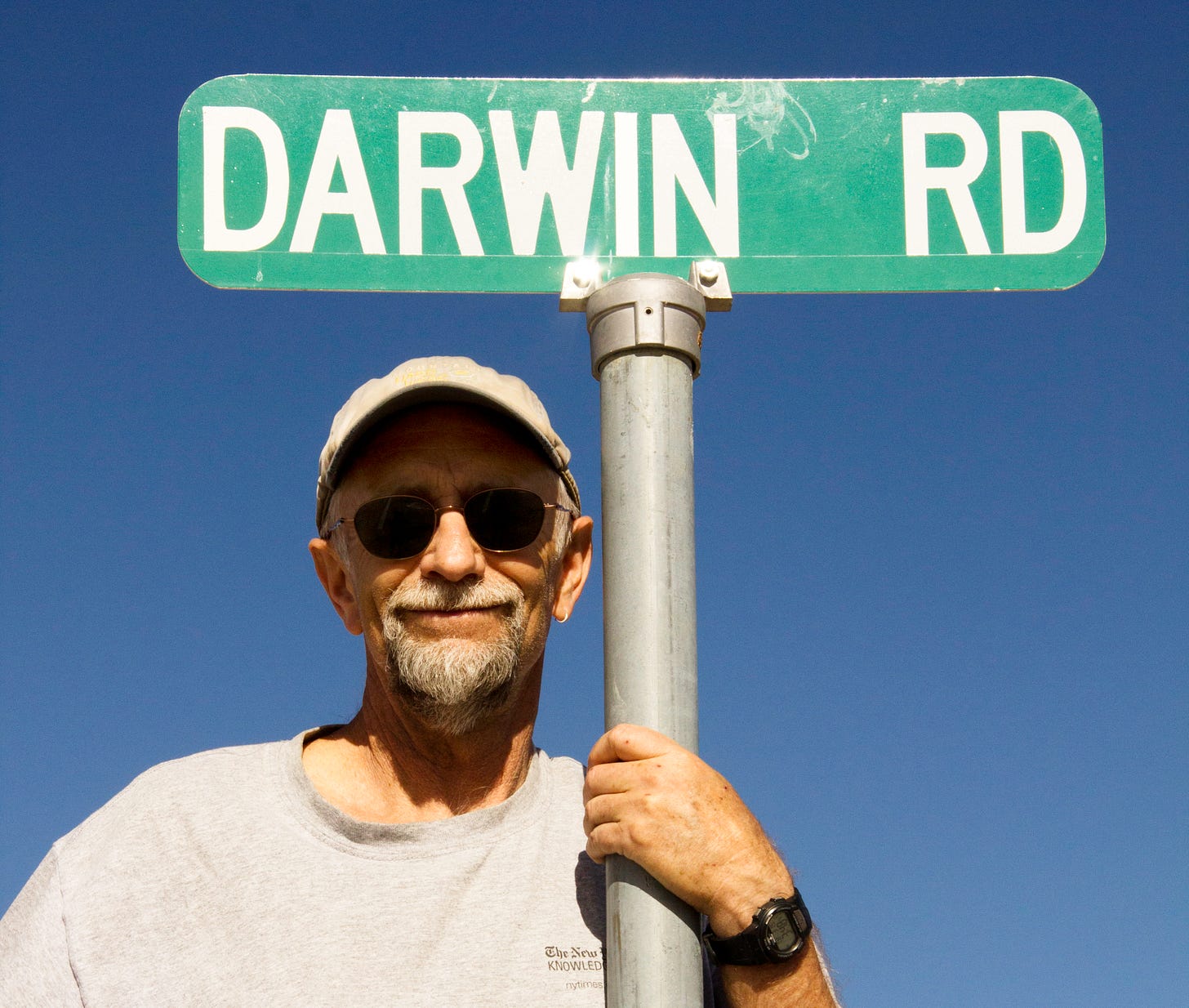

Finally, our two cats (okay, not people, but . . .), Darwin and Wallace, have helped me feel settled here. They’re both rescue cats (one from Flowood, one from Pearl). Darwin especially has helped me appreciate the Mississippi environment, through our daily walks. He’s made me pause and be present in this place, which has been a real blessing.

Another process that’s helped me feel more rooted here is immersing myself in Mississippi’s natural environment. Visiting beautiful places such as the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge, running at LeFleur’s Bluff, learning to love the deafening thrum of cicadas on a summer evening, listening to a Carolina Wren’s morning song, or finding a swamp rose-mallow blooming at the edge of Mayes Lake: these things, and many more, have helped me feel settled.

What’s the weirdest question or assumption you’ve encountered about Mississippi (or about you as a Mississippian) by someone who’s never been here?

The assumption that most everyone who lives here is in some way benighted, and that Mississippi is mostly a backwards state. When I told folks in New York that I was moving to Mississippi, many were quietly shocked: “Why would you do that?” The only people who didn’t respond in this way were my close friends and several people who previously had lived in Mississippi and who had a better understanding of the positive and negative aspects of the state.

Another important realization is that in Mississippi history feels much more alive and fully present than anywhere else that I’ve lived. Maybe this sense is partly a function of my preoccupations when I lived elsewhere, but slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights conflicts of the 1950s and 1960s: their fallout, the long skein of history, just cannot be ignored, much as some people would like to.

How has living in Mississippi affected your identity and your life’s path?

Ten years ago, if someone had suggested that I’d move to Mississippi and buy a home here, I would have shaken my head in disbelief. Yet here I am, and I’m happy. Life can take us in such unexpected directions; that’s a cliché, but it’s still true. Another thing: at seventy-three I’m firmly planted in geezer-hood, which can lead to emotional and intellectual ossification—so moving to the Deep South has been helpful in keeping me open to adventure and personal change. I’ve had to adapt, which is a good thing.

And now that I’m a Mississippi resident, I find that it’s becoming part of my identity. So, I can get my back up when I’m traveling, and people look at me askance when I tell them I’m from Mississippi—I might as well have said that I’m from Moldova or the planet Tralfamadore (from the Vonnegut novels). I resent people stereotyping the state; yes, Mississippi has a blood-stained history and is rife with economic and social problems, but there also is much that’s good about the place—and many of Mississippi’s problems are shared by other parts of the country.

What is something that you’ve learned about Mississippi only by living here? In what ways has Mississippi lived up to your expectations?

I had few expectations about Mississippi when I started visiting, other than that the summers would be tough—plus some stereotypes that I’ve mostly discarded as I’ve become more familiar with the state. I’ve been surprised by how friendly and polite most people are, and by the rich art and music scenes in the area. There’s so much going on! Another important realization is that in Mississippi history feels much more alive and fully present than anywhere else that I’ve lived. Maybe this sense is partly a function of my preoccupations when I lived elsewhere, but slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights conflicts of the 1950s and 1960s: their fallout, the long skein of history, just cannot be ignored, much as some people would like to. And I believe that this historical presence—this force—is ultimately a good thing, for the only way in which people can heal, whether individually or as a society, is to face the past and deal with it honestly and openly, rather than by forgetting or insisting that “things were better then.” Only problem is, I have no idea as to how society can do this. So, one must start with the individual.

Ten years ago, if someone had suggested that I’d move to Mississippi and buy a home here, I would have shaken my head in disbelief. Yet here I am, and I’m happy.

Have you ever thought about moving away? Does a sense of duty keep you rooted here? Do you have a “tipping point”?

I just moved here, so I’ve not thought about moving away, and right now I would hate to do so. The only plausible reason for moving that I can imagine would be if my partner takes a job elsewhere in the country. As far as “tipping points” go, I don’t know. Give me a few more years here and maybe I’ll have a better idea about those.

What do you wish the rest of the country understood about Mississippi?

That despite Mississippi’s history and image, there are many good things happening here, and many good people. Yes, there are also huge problems—but to some extent every part of the country has similar issues, or at least equally difficult and seemingly intractable ones.

Do you have a favorite Mississippi writer, artist, or musician who you think everyone needs to know about?

In terms of writers, I am very fond of Jesmyn Ward, Kiese Laymon, W. Ralph Eubanks, and Natasha Trethewey (sorry, more for her essays/memoir than for her poetry), and Eudora Welty. And although he only lived in Mississippi for a short while, Richard Grant wrote a great book about the Delta country, Dispatches from Pluto. In terms of music, Mississippi John Hurt, Muddy Waters, and John Lee Hooker. And although I don’t like all their music, The Chambers Brothers’ “Time Has Come Today” will always resonate, because it was a “song of the times” for me. I still can recall the first time that I heard it, way back in 1968.

If you had one billion dollars to invest in Mississippi, how would you spend your money?

How about five billion dollars? Please? Whatever the amount, I’d invest a good portion in public K-12 education, because the state legislature and governor refuse to adequately fund public education at that level. I’d also create a large endowment for Mississippi Today, because we need strong, independent investigative journalism, to expose travesties such as the Rankin County “Goon Squad” and the welfare scandal involving Phil Bryant, Brett Favre, et al. I’d provide a healthy endowment for the Jackson Free Clinic, which serves those in Jackson without health insurance. I’d also give a substantial amount of money to the Mississippi Humanities Council, because unlike Shad White (state auditor and politician on the make), I believe that Mississippi needs more humanities, not less. And I say this a scientist. Finally, I’d give money to an organization that promotes constructive dialog among all the people of Mississippi—rich and poor; straight and LGBTQ; Black, white, Hispanic, Asian American, and Native American; Democrat and Republican, on and on.

What or who do you want to shamelessly promote? (It can absolutely be a project you’re working on, or something you are involved in.)

I guess that I would shamelessly promote my three books of creative nonfiction that are in print: Relicts of a Beautiful Sea: Survival, Extinction, and Conservation in a Desert World (2014); In the Memory of the Map: A Cartographic Memoir (2012); Return to Warden’s Grove: Science, Desire, and the Lives of Sparrows (2008). I’ve just finished another manuscript, A Field Guide to Senescence, which is about aging; now, I am looking for a publisher or agent for the dang thing.

Chris Norment is an emeritus professor of environmental science and ecology at the State University of New York - Brockport. He enjoys poking around wetlands, deserts, mountains, tundra, and other wild places of this earth. In 2023 he moved to Jackson, Mississippi, where he lives with his partner and two cats. He is the author of four books of creative nonfiction, most recently Relicts of a Beautiful Sea: Survival, Extinction, and Conservation in a Desert World. His website is at christophernorment.weebly.com.

One year ago:

Mississippi Transplant: Tyriek White

"I often call Mississippi home and it stuns people, even though I’ve been here for a while. It is a life I’ve built on my own, a form of refuge."

Two years ago:

Mississippi Expat: Dennis Jay Johnson

"While I don’t visit as often as I would like, Mississippi represents a beginning. I learned to read music, drive a car, and later attended college there. In this “origin story,” which happened in no small part thanks to my family, I find myself incapable of separating Mississippi from home."

Jackson is lucky to have you and Eli here! As another member of the geezer-hood cadre, I'm particularly eager to read A Field Guide to Senescence and hope you find a publisher soon!

Great interview. I would love a visit with him on the porch at the farm’s Grateful House!