Mississippi Native: Snowden Wright

"That’s how Mississippi has affected my identity. It made me a novelist."

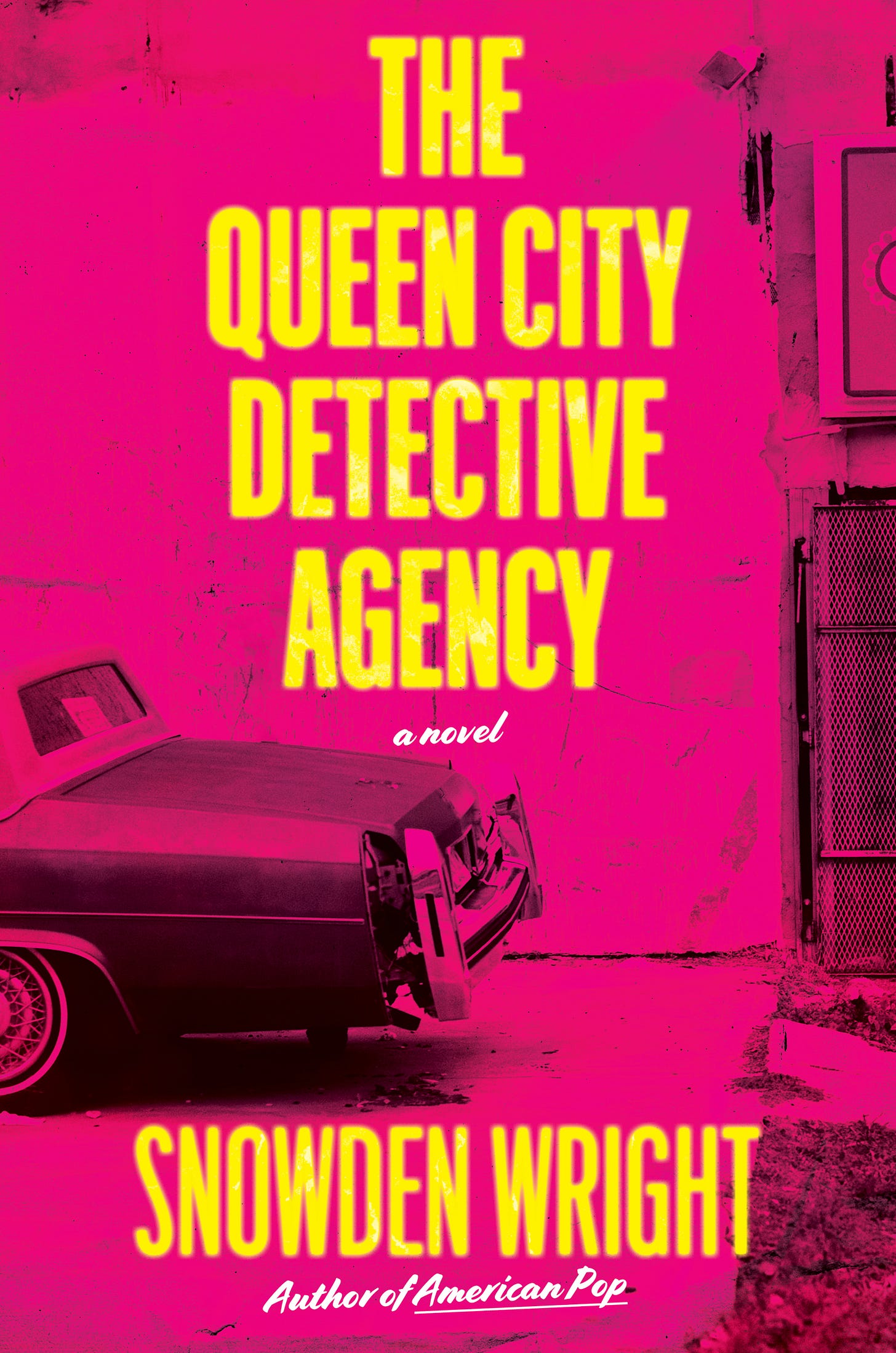

What does it mean to call Mississippi home? Why do people choose to leave or live in this weird, wonderful, and sometimes infuriating place? Novelist Snowden Wright fled Mississippi—and his hometown of Meridian—when he left for college in the Northeast. “I wanted to exile myself from home so I could better understand what home had done to me,” he writes. While stalled on the writing of his second book, he moved from New York City back to his home state. After a stint in Atlanta, he now lives and writes from his home on his family’s farm in Yazoo County. Snowden’s newest novel, The Queen City Detective Agency, which follows a jaded female P.I. enmeshed in a criminal conspiracy in 1980s Meridian, MS, is forthcoming in August. Below, Snowden tells us what keeps him rooted in Mississippi.

Where are you from?

At the center of a loosely affiliated crime circuit between New Orleans, Birmingham, Jackson, Biloxi, Phenix City, and Atlanta sits Meridian, Mississippi, the state’s erstwhile “Queen City,” where white supremacists plotted the “Mississippi Burning” murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in 1964; where the KKK bombed a synagogue in 1968; where, in dive bars, truck stops, and no-tell motels, the infamous Dixie Mafia conducted its extra-legal business of drug-trafficking, numbers-running, loan-sharking, election-rigging, racketeering, prostitution, extortion, protection, and assassination.

That’s where I’m from.

But also in Meridian, Mississippi, James Meredith began a legal campaign against Ole Miss that eventually led to the state university’s integration. Also in Meridian, Mississippi, after the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, an all-white jury convicted seven people, including a white deputy sheriff, the first time in the history of the state a white jury has convicted a white official on civil-rights charges. Also in Meridian, Mississippi, progressively minded individuals live and work and strive for progress in a too-often and too-easily maligned city and state.

Why did you leave Mississippi? Where did you go?

In Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce writes, “I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defense the only arms I allow myself to use—silence, exile, and cunning.” My decision to leave Mississippi for college as a young man who was neither cunning nor silent perforce involved exile.

I wanted to exile myself from home so I could better understand what home had done to me. I wanted to figure out who I was, what Mississippi had created.

To my myopic teenaged mind, Meridian felt like a Dixie Jonestown. Everyone had eaten the Kool-Aid pickle. In Hanover, New Hampshire, essentially another planet to some kid who didn’t even know how to use chopsticks, I wanted to surround myself with people from all over the country and all over the world. I hoped to encounter new modes of thinking, a broader sense of culture, and a diverse range of life experiences.

And I did encounter those things. I was surrounded by all kinds of people. I also spent a lot of time explaining to those people that, yes, you can make pickles with Kool-Aid.

Why did you return to Mississippi?

Back in 2014, I was living in New York, working on my second novel, American Pop, while also working a full-time job. The book was taking forever to write. Every day I woke up at five in the morning to work on it before heading in to the office. Then, sadly, my grandfather passed away. With the small inheritance he left me, I decided to honor his memory and his generosity by using the money to quit my day job and return to the state he’d lived in his entire life.

I spent a year and a half in Oxford, Mississippi, writing full-time. Was it an amazing experience? Of course. Do I realize how fortunate I was? Absolutely. Did I decide to stay in Mississippi? Nope!

After finishing the novel, I moved to Atlanta, where I worked a day job once again. The sale of my second and third novels enabled me to not only quit that job but also build a house on my family’s farm in Mississippi. For the house site I chose the spot in a pecan grove where my grandmother’s childhood home had stood before it burned down. The construction crew literally had to dig up the foundations of her house before I could put down my own.

I’ve been living in Yazoo County, Mississippi, maybe for the long haul, since the start of 2020.

I wanted to exile myself from home so I could better understand what home had done to me. I wanted to figure out who I was, what Mississippi had created.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rooted Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.