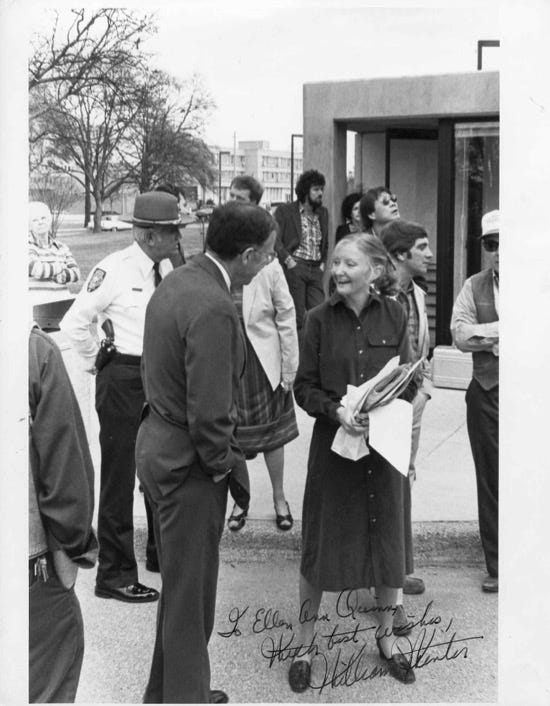

Mississippi Native: Ellen Ann Fentress

"Mississippi is a living organism, I think. It pulses with people I love, time, nature, community, hope, hurt, creativity and all the associated intersections."

What does it mean to call Mississippi home? Why do people choose to leave or live in this weird, wonderful, and sometimes infuriating place? Today we hear from writer, journalist, and filmmaker Ellen Ann Fentress, whose memoir The Steps We Take: A Memoir of Southern Reckoning comes out this fall.

Where are you from?

Greenwood

How long have you lived in Mississippi?

Always. I grew up in the Delta, then Jackson since age 18, bisected by four years on the Gulf Coast in Pass Christian and Biloxi in my twenties.

What does home mean to you?

A space that you get, and it gets you—at least enough of the time. You know you’re home when your sense of being and insides exhale, and your body unthinkingly sinks into the moment. Home can happen inside your actual home or in the other ways too—being with your people, being outside or sometimes while being caught up inside your own head.

How does Mississippi meet that definition?

There’s layered back story that comes with almost everything here, a reality that you and everyone around you realize. Mississippi is a living organism, I think. It pulses with people I love, time, nature, community, hope, hurt, creativity and all the associated intersections.

I love the cycle to how life happens here—like Joni Mitchell’s song “The Circle Game.” January starts with a pot of black-eyed peas while simultaneously holding vague hopes that somehow this will be the year the Mississippi Legislature does something humane and historical. Then comes February with lipstick-red camellias, an inevitable freeze and the outer bands of New Orleans Mardi Gras. Also by then the Legislature has broken your heart for yet another session and probably made national news over some grotesque bill plus the headline-making associated quotes. The quotes will come from a white lawmaker. Then comes March and the open-air magenta floor show of azaleas in every front yard and bank branch parking lot. Your heart breaks again, but this time it’s over the lavish casual beauty everywhere and not solely the lavish callousness of the majority at the Capitol. Then there’s spring and summer—you get the idea.

That’s a hard part of Mississippi, to know what’s home for me doesn’t seem a fit nor even advisable for too many Mississippi-born millennials.

Fall goes fast: Mississippi football teams and the New Orleans Saints. Then Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur—I’m Episcopalian and my partner is Jewish—yellow slanted sunlight in October and piercing blue skies. Trick or Treaters on my block in Jackson’s Leftover neighborhood (named because we’re adjacent to top-drawer Eastover, but we’re so not Eastover). Going to Mistletoe Marketplace in early November and seeing people you haven’t seen in a minute along with pretty much every church bus with a working engine in the state. Then orchestrating Thanksgiving and Christmas, now more complicated since my two daughters, like so many other Mississippi-born millennials, left the state after college. That’s a hard part of Mississippi, to know what’s home for me doesn’t seem a fit nor even advisable for too many Mississippi-born millennials. Then back to the New Year’s black-eyed peas, and the cycle starts back around.

Did that all that sound saccharine? Yes it did. I have digital backup, though. The FitBit says my pulse relaxes here at home on a plain old day in a way it doesn’t elsewhere. Also, last time I did a word cloud quiz on Facebook, my most frequent word was Mississippi.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rooted Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.