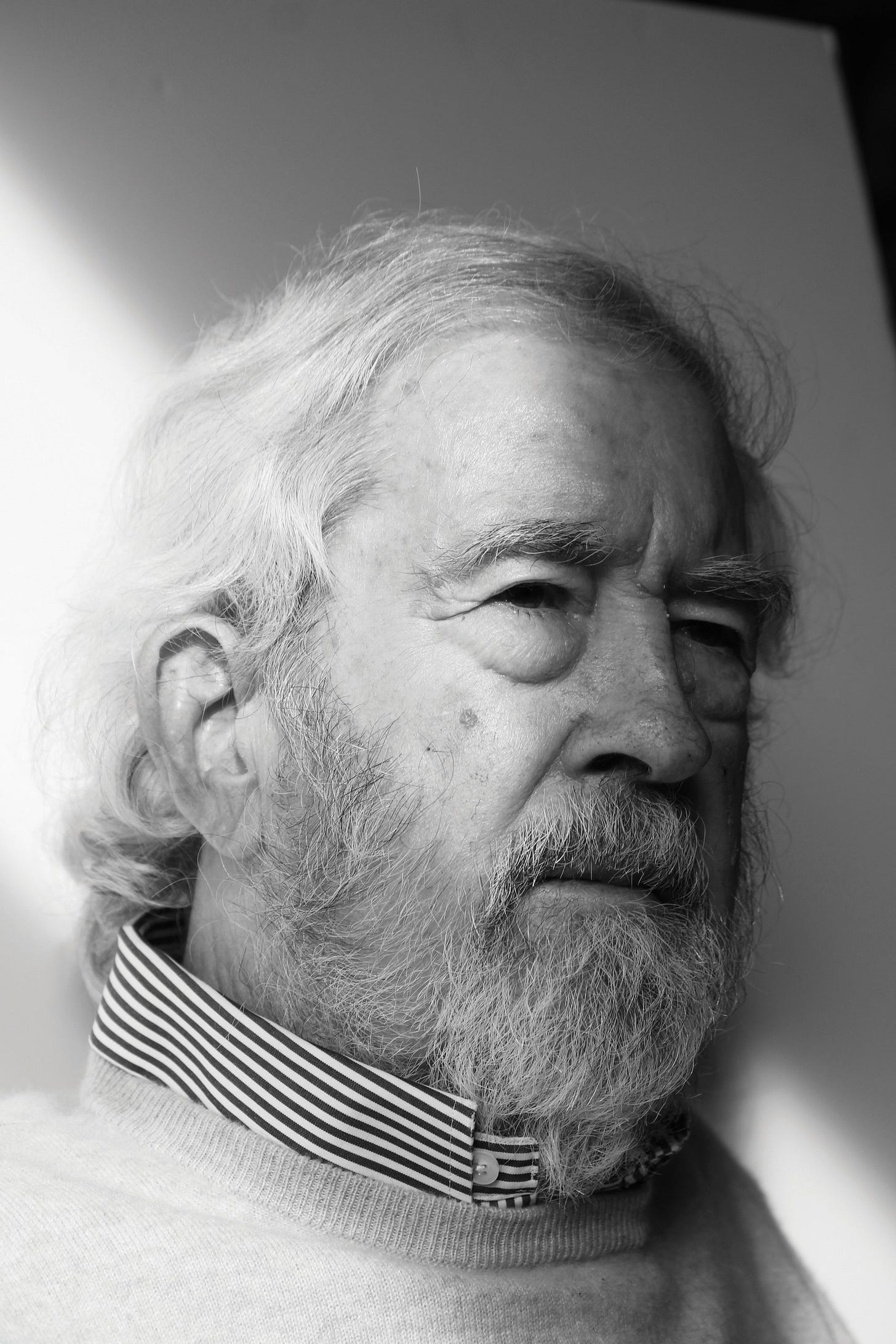

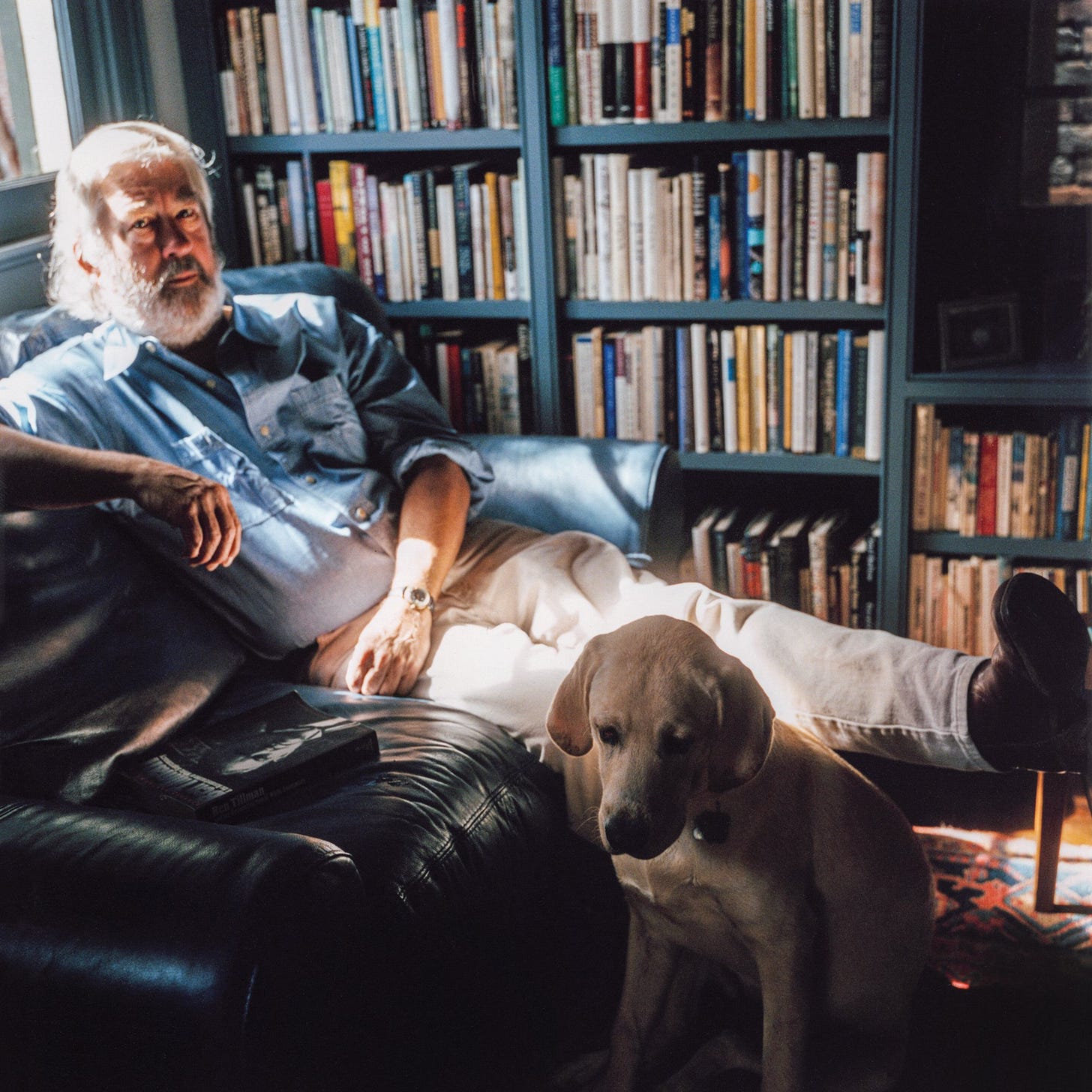

Mississippi Native: Curtis Wilkie

"[Willie Morris] would write me letters and say, 'It's time for you to come home, boy.' I eventually did."

What does it mean to call Mississippi home? Why do people choose to leave or live in this weird, wonderful, and sometimes infuriating place? In October, ahead of the election, I spoke with award-winning journalist, author, and professor Curtis Wilkie. Curtis is the author of multiple books, including When Evil Lived in Laurel: The White Knights and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer and Dixie: A Personal Odyssey through the Events That Shaped the Modern South. After retiring from The Boston Globe, he went on to teach hundreds of journalism students during his tenure at the University of Mississippi’s Charles Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics. Curtis was a delight to talk with, a natural storyteller with a humble and generous spirit. He spoke about the liberation he experienced leaving Mississippi behind as a young man with big ambitions, and the eventual tug he felt to return home. “I always loved the state. I never denied I was from Mississippi. I was asked with my accent, ‘Where are you from?’ I'd always volunteer, ‘Mississippi.’” The following interview has been edited for length and clarity. Later this week, paid subscribers will get access to the full recorded interview with Curtis.

Where are you from?

Right now I'm living in Oxford, Mississippi, and I have been here for a bit over twenty years. But I lived a number of places in Mississippi, different regions for that matter. I was born in Greenville in the Delta. I really grew up in a small town in South Mississippi called Summit, then graduated from high school in the far northeastern corner of the state at Corinth, and then went to school at the University of Mississippi. I then worked in Clarksdale for seven years after graduation as a young reporter. So, I kind of lived all over in the state before I left. Since I came back, I've been fixed in Oxford.

Why did you leave Mississippi and where did you go?

I left like a lot of people in the ‘60s because the politics in Mississippi made me very uncomfortable. I’m admittedly a liberal, which in some circles in Mississippi equates to being a communist, or something like that. Mississippi had been terribly uncomfortable for the Black population throughout the ‘60s. And of course, so many people left the state during what was called the Great Migration earlier in that century. But I think the stifling atmosphere in the state drove a lot of white people away too.

Willie Morris, who became a very good friend of mine, wrote a wonderful book about that called North Toward Home. He had grown up in Yazoo City, Mississippi, and he left and he wrote very movingly about his affection for the state, but also about the problems that he felt existed here that made it a place where he didn't think he wanted to live. That book, which came out in the mid-1960s, was very influential to me as I was evolving myself.

We drove to Washington with my little family—my wife at the time and two children, both small, were in the car—and as we crossed the state line into Tennessee, I said, “Free at last, free at last. Thank God almighty, free at last.” I couldn't imagine that I would ever come back. And it was a long time that I was away.

I had covered the Civil Rights Movement and was very sympathetic to it. So, eventually, in the late ‘60s, I began trying to figure out how do I leave the state. And I applied for and received a congressional fellowship in 1969 from the American Political Science Association. I moved to Washington and [worked] on Capitol Hill for a year under the fellowship. I thought I was gone for good.

We drove to Washington with my little family—my wife at the time and two children, both small, were in the car—and as we crossed the state line into Tennessee, I said, “Free at last, free at last. Thank God almighty, free at last.” I couldn't imagine that I would ever come back. And it was a long time that I was away.

But I always loved the state. I never denied I was from Mississippi. I was asked with my accent, “Where are you from?” I'd always volunteer, “Mississippi.” I never lost my accent in all the thirty years that I lived away.

Why did you return to Mississippi?

One gets very conflicted, and Willie Morris was conflicted. And I was conflicted. And Willie, as I said, became a good friend. By that time, he had moved back to Mississippi, and he was one of the people encouraging me to come home. He would write me letters and say, “It's time for you to come home, boy.” I eventually did.

I was troubled by things that went on here. I still am. But I'm very happy to be back. I had many friends down here and visited either my relatives or my friends in Mississippi down through the years. And finally, it was an easy decision that I made.

I did it in stages. I didn't move back to Mississippi; I moved to New Orleans, which was the city that I was close to growing up in South Mississippi. So I moved back to New Orleans in 1993 and continued to get closer to Mississippi. [The Boston Globe] let me establish a southern bureau, to cover the South in general. And so I did a lot of stories in Mississippi and I felt there'd been a lot of progress made. And that's one of the reasons I moved back. I've been very, very happy in Oxford.

Having said that, I’m not happy with a lot of the things going on in the state again. I think we have reverted badly over the last ten years or so.

I'd say unquestionably that's the best thing about Mississippi: people are nice here.

Did it feel like you were returning to a different place when you moved back?

Oh, yes. Particularly when I came to Oxford. By then I had retired from The Boston Globe and was living here. I was approached [to see] if I was interested in teaching at Ole Miss, and I accepted readily.

For years I was estranged from my alma mater because of the events that took place here in 1962, which was my senior year, when James Meredith finally was enrolled at the price of a terrible riot on campus. [The backlash] was a stigma to the school. And I had nothing to do with Ole Miss for years and years.

And then I saw the good things that were happening at the school when I was living in New Orleans, and I saw how attractive Oxford was. And that's why I came. I would not have gone back to Ole Miss and joined the faculty had it been like it was when I was a student. The academic leadership had abdicated and let the governor essentially take control of the school in 1962 and defied the federal government and brought thousands of troops onto the campus where they stayed for months. I had to go through military checkpoints to get on campus. Thank you, Ross Barnett and the Citizens Council. Certainly the Ku Klux Klan was involved in the riot.

But then we had progressed with better chancellors and better people and what I believe is a very well-rounded faculty.

A history professor at Ole Miss, Jim Silver, wrote a book called The Closed Society, and that's what we were, we were a closed society. It hasn't reached that extreme yet, but it's moving in that direction now. The state college board is very punitive and basically refused to renew the contract of a wonderful chancellor we had. And the school went into a stagnant situation for several years. That was about ten years ago. So it's discouraging what's going on here now. But I'm not going to leave. I'm too old to leave at this point. I've got too many friends.

How have you cultivated community in Mississippi? Who are the people who have made you feel rooted here?

Oh, in many cases, friends from my school days. Some of them don't necessarily agree with my political views, but they're friends, and we do things together. Here in Oxford I was invited to join a small group that gets together once a week for lunch. I'm by far the most liberal member of the group. We don't really argue. I just enjoy being with them. They're virtually all conservative people. Probably most of them are going to vote for Donald Trump, but there's not a single one in that group that I don't enjoy going to lunch with.

Then there are a lot of my former students who are around. One of my former students is editor of Mississippi Today, Adam Ganucheau. He’s become a good friend. And I'll have to say that my family—my daughter Leighton and her husband Campbell and their three wonderful boys—lived here in Oxford for many years. They've moved eight miles away, but that's a great thing, too.

What’s the weirdest question or assumption you’ve encountered about Mississippi (or about you as a Mississippian) by someone who’s never been here?

I think that we're immediately stamped as being still loyal to the Confederacy. We're typecast simply with our accent. People assume that we're uneducated. I certainly ran into a lot of incredible condescension when I lived in Boston. Simply, if I'd opened my mouth, they would say, “My God, where are you from?” They not only have that attitude toward me, but toward the whole state. The state certainly has helped develop that bad image. But not everybody who lives here is an idiot.

I was troubled by things that went on here. I still am. But I'm very happy to be back.

What is something you’ve learned about Mississippi only by living here?

Oh boy, that's a good question. As I've learned and said very often, especially after I was beginning to move back here, it’s the importance of being civil and kind to people. I put this in my book, Dixie, and Willie Morris figures in it. We were at a dinner in Jackson and everybody had had a good bit to drink. Eudora Welty was one of the people at the dinner, a small group of people in Jackson.

Probably around midnight, we're still sitting around the table, and Willie asked me, “Curtis, why did you come home?” I'd been wrestling with this question. I blurted the answer. I said, “Because people are kinder here.” And I truly believe that. People are nice, with a few exceptions, obviously. But it's just a kind environment to live in, I learned, particularly after living in some of those very busy and spiritually cold, famous eastern cities where people weren't necessarily kind.

I think it's like osmosis, that I hope it has helped me to be a kinder person. I try not to be rude. I try to be tolerant. All the characteristics of being a liberal that you read in the dictionaries: that a liberal is tolerant, that a liberal is accepting of change and different views—a long way from Marxism or something that people would attribute to liberalism. I'd say unquestionably that's the best thing about Mississippi: people are nice here.

You've known a lot of writers and artists, but do you have a favorite Mississippi writer, artist, musician, or creative you think everyone needs to know about?

Immediately, I think of friends. Largely, there are some people I don't know who are writing and doing very well. But my friend Richard Ford, who grew up in Jackson. Even though he doesn't use Mississippi or necessarily the South, as the setting for his work. Richard's a Mississippian, and I think he's one of the great novelists.

I just finished a very powerful book by Oxford writer Wright Thompson called The Barn. I think Wright is one of the best writers living in the state right now. The book is sweeping, using the murder of the little boy Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955 as the centerpiece, but it's so much bigger than that. It's well researched and well reported and it's the best book I’ve read this year. There are so many people who are writing good books, and it's one of the joys of living in Oxford.

I think of my friend Bill Dunlap, who's been around for years. And certainly the musicians from the Delta who transformed American music. Virtually all of them were Black. When I was a teenager, it was the time when you had this incredible movement and people like Bo Diddley, who was from McComb (which is basically where I grew up), and Little Richard, Fats Domino. The woods are full of famous people in Mississippi.

I never denied I was from Mississippi. I was asked with my accent, “Where are you from?” I'd always volunteer, “Mississippi.” I never lost my accent in all the thirty years that I lived away.

If you had one billion dollars to invest in Mississippi, how would you spend your money?

I'm a journalist, that's how I spent my life. I would invest it in journalism in Mississippi and all the little newspapers that have given up, that no longer operate. I would certainly invest it in Mississippi Today because it's proved to be a modern success. They’d probably be the number one recipient. If the population no longer knows what's going on, then the political leaders can do what they want to.

What a great interview. Years ago at the dedication of the Meredith monument at Ole Miss Deb and I accompanied Will Campbell to Mr. Wilkie's home for a reception. A real treat to be like a fly on the wall and see and here folks like Will, Curtis, Morgan Freeman and others visit!

"... people are kinder here.” Yes!

"The woods are full of famous people in Mississippi." And, yes!

I love this interview so much. It gave me chills. Thank you, Lauren. Thank you, Mr. Wilkie.