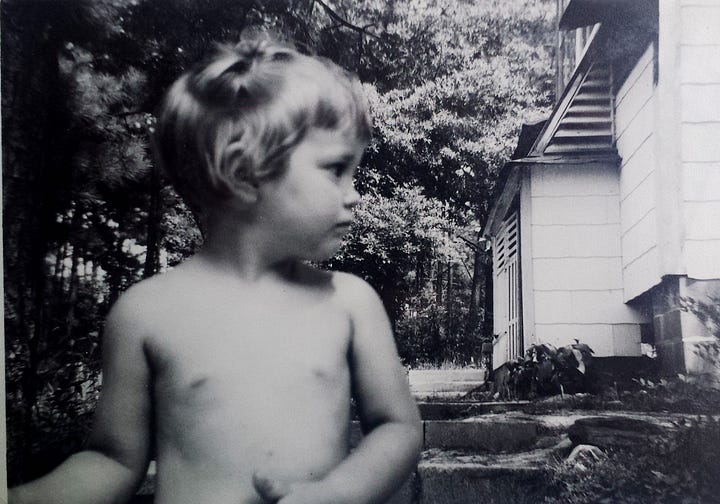

Mississippi Native: Bebe Wolf

"Home for me has always meant this place where I grew up. And the fact that it's in Mississippi is kind of an accident."

Earlier this month, I spoke with Bebe Wolfe, an artist and the owner of Wolfe Studio in Jackson. Founded in 1946 by Bebe’s parents, Karl and Mildred Nungester Wolfe, the Wolfe Studio has been a hub for Mississippi art and artisans for over seventy-five years. Bebe grew up in this oasis, surrounded by her parents’ art and the gardens her father planted. After taking on her role as steward of Wolfe Studio, Bebe and her husband, David Weidemann, also designed and built a meditation dojo on the studio grounds. The Dojo serves as a hub for Zen and meditation groups that regularly meet there. Connection to place, to the landscape, and to her family are themes that Bebe returned to throughout our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity. Paid subscribers will get access to the full recorded interview with Bebe Wolfe later this week.

Where are you from?

I was born and raised right here. I’m sitting in the kitchen of my parents' house [in Jackson] where I spent my childhood and went off to college in Maine for a few years, met my husband there came back, brought him back. So I've been pretty rooted in this spot.

Was living in Maine the only time you lived outside of Mississippi?

I did live briefly in New Orleans when I was in my twenties, which was an interesting experience, but didn't come out too well, so I ended up back home. I was thirty when I decided I would go off to art school and found this school in Maine. It was then called Portland School of Art. It's now called MECA, Maine College of Art.

I was there for five years. It was a four-year school, and then I stayed on for another year, thinking that I was going somewhere very, very different from Mississippi. And in some ways, it was very, very different, but in other ways, it was not, because Maine is also a mostly rural state with quite a lot of rural poverty. In the 1980s it was a pretty hard-bitten place in a lot of ways.

I was in Portland, and Portland grew and prospered, changed a whole lot for the four years that I was there. There was an amazing change going on with people from New York and Boston traveling up, establishing businesses in Maine. So it was an interesting time, and I loved it.

What made you want to return to Mississippi?

My father died in 1984 and that was the year I graduated from school. We didn't expect him to pass so early and I was concerned about my mother. My mother was about eight, nine years younger than my father. And she was still going great guns with the studio and her painting. She was a lifelong artist, but she was never a very social person. She was very centered on her art and her family, and I was worried about her being alone. I really wanted to come back and be with her.

I had met my husband, David Weidemann, in Maine, and we married the next year, in 1985. I was able to talk him into coming down to Mississippi. And that began our adventures here, coming back together as a married couple.

My mother was very independent for a while, but she became more dependent on us. We were able to buy the adjoining property that was further up the hill from where the studio is, and that was a godsend because I could just walk down the driveway and see my mother and take care of her and take care of the studio. She was still making the ceramics, the birds, when I came back. And she was pretty determined to keep doing it. I tried to talk her into letting that go, but she was very determined.

Growing up, my father used to talk about how we artists were a little different from other people, very lucky to be able to be doing what we were doing, living in this beautiful, secure location. I think all that attracted me back.

It always had been a kind of a bread and butter process, a trade for my parents, because they were both painters. They were determined to keep the studio going as a way to make a livelihood. When they first were here in the 1940s, there was no place to sell art, no other galleries or anything that could represent them. They wanted to represent themselves, and have the studio be a place for people to visit. And they discovered ceramics early on in the 1950s.

I grew up being sort of pressed into service. They would give me a lump of clay and say, make a bird, you know, make something. And I'd make some lumpy little thing and they'd say, “oh, it's great!” And they would refine it a little bit, make a mold of it, start selling.

When I was away in Maine, I felt nostalgic for the place, because I grew up here and I felt like it was a real oasis, a peaceful home to come back to. Growing up, my father used to talk about how we artists were a little different from other people, very lucky to be able to be doing what we were doing, living in this beautiful, secure location. I think all that attracted me back.

And then when we were able to buy the property adjoining and then my mother needed us to be here, those things anchored me to this spot. At some point, my mother could no longer really run the business. And David and I took it over and became partners running the business. That overrode any other ideas that I might have had of going off and doing something else because there was so much to do right here.

Was the Mississippi you returned to the same one you had left?

I've thought about this a lot: when you stay in one place, you see change in a different way. When I moved back here from Maine, I felt in my heart like I was coming back to a place that didn't change, that it was all going to be just like I remembered it. And then, of course, it changes. Year by year, it changes.

Coming back to a place that you remember and are familiar with, you see the change happen a bit more vividly than you do if you move around. You move somewhere, it's all new, and you take it just as it looks, just as you experience it. You don't have the deep memory of how it has become what it is. Whereas if you stay in one place, you have a memory of the trees being smaller, the place being sunny once where it didn't have such big trees. The living landscape you see changes over time. You also have the benefit of knowing people for a very long time and seeing how they change.

Coming back to a place that you remember and are familiar with, you see the change happen a bit more vividly than you do if you move around. You move somewhere, it's all new, and you take it just as it looks, just as you experience it. You don't have the deep memory of how it has become what it is.

What does “home” mean to you? How does Mississippi fit into that definition?

Home for me has always meant this place where I grew up. And the fact that it's in Mississippi is kind of an accident. I mean it could have been anywhere else but my attachment to this particular place is so tied in with all my childhood experiences and my parents’ experiences and how much they loved this place, the things they planted.

My father was a great gardener. What he planted is still thriving, growing bigger. Everything changes all the time, but it still has the feeling, the landscape of home, and I know it very intimately. And that's an experience a person could have anywhere—it didn't have to be Mississippi necessarily. And the fact that it is Mississippi has always been a little bit incidental in my mind.

How have you cultivated community in Mississippi? Who are the people who have made you feel rooted here?

I grew up in an artistic family—we always cherish the outsiders, people who are not quite in the mainstream. So those are the people that I feel are my family; they make me feel at home. We speak the same language in many ways. We understand each other. Having this place, the studio and people knowing about the studio, coming to the studio, buying things and all that—it kind of gives me a cover to explore my own thoughts, explore my own feelings, my own direction with art and also with meditation and Buddhist practice. That's not my public face, but I feel completely free within that to pursue my own thing, to go my own way. And I don't know what that's like for other people here in Jackson, but I'm hoping people feel the same freedom in pursuing their heart direction. There are a lot of creative people in Jackson who are doing that.

Home for me has always meant this place where I grew up. And the fact that it's in Mississippi is kind of an accident.

What’s the weirdest question or assumption you’ve encountered about Mississippi (or about you as a Mississippian) by someone who’s never been here?

That question makes me think of my time in Maine. Everybody knew I was a Southerner because of my accent, but people couldn't quite imagine where Mississippi was. They knew where Florida was, but Mississippi was sort of behind the Magnolia Curtain.

Do you still think about moving away someday? Does a sense of duty keep you rooted here? Do you have a “tipping point”?

At this point in my life (I'm about to be seventy-six in May), I think I'm pretty much stuck here. I can't quite imagine uprooting, really. I have dreams of being able to spend more time in Maine because I loved it, and love the summers. Perhaps I'd be able to do that someday, be able to migrate a little bit back and forth, but as for relocating I don't think that will happen. When I was younger, I thought about it a little bit, but I'm so embedded here with my business and with the meditation, with this beautiful place. It's just hard to imagine being somewhere else.

Mississippi is just full of people. It's like everywhere else. And people have greatness in them and they have meanness in them. And if there are ways to encourage the greatness, then you'll see it come out.

What do you wish the rest of the country understood about Mississippi?

The rest of the country needs to understand that poverty is the greatest ill in Mississippi. That is not something that is unique to Mississippi—it is a problem everywhere. The nature of poverty, how multi-generational poverty keeps things going and keeps things the same and the power structures that keep things the same—that's what produces both the ills that Mississippi deals with and also, in some ways, the sparks of real creativity, of things busting out, like grass growing through the cracks in the cement. Mississippi is just full of people. It's like everywhere else. And people have greatness in them and they have meanness in them. And if there are ways to encourage the greatness, then you'll see it come out.

Do you have a favorite Mississippi writer, artist, or musician who you think everyone needs to know about?

Well, I have to say my favorite would have to be Eudora Welty because I knew her. She and my mother were friends, and I was able to hang out with her a little bit. She was not only an outstanding writer, but she was such a gracious person and fun to talk to, and also every bit herself. She was at home being who she was. You meet someone that way, like that, and it helps you, helps your spirit.

Do you have a favorite Eudora Welty story?

My mother, of course, knew her more than I did, and my mother told the story about her. My mother grew up in Alabama, and she was in Alabama once, not in her hometown, but I think in Montgomery, visiting somebody, and Eudora was giving a reading there in Montgomery, and my mother went. And when Eudora looked up and she saw my mother, her face just burst in a smile, this big smile to see her. And my mother felt that so deeply, that here was this important person focused on giving her reading, but she interrupted the reading to just look up and see her, and was so happy to see her. That was so much like Eudora, to be this natural. And it touched my mother.

The nature of poverty, how multi-generational poverty keeps things going and keeps things the same and the power structures that keep things the same—that's what produces both the ills that Mississippi deals with and also, in some ways, the sparks of real creativity, of things busting out, like grass growing through the cracks in the cement.

If you had one billion dollars to invest in Mississippi, how would you spend your money?

Well, I would have to think about that really hard. But I'd like to do something to help the health system in Mississippi. I don't know if a billion dollars would be enough. And the arts. The Arts Commission does a wonderful job, and I appreciate every bit of the work that the Arts Commission does. There's so many talented people, both alive, present, and past in our state that I wish could be celebrated more. If I had a billion dollars, I'd love to set aside some of it for an endowment to create databases of people's work, accomplishments that could be accessed, so there would be people not necessarily represented in museums at all, but where their work could be visible.

What or who do you want to shamelessly promote? (It can absolutely be a project you’re working on, or something you are involved in.)

We've created a nonprofit called the Wolfe Creative Legacy that is aiming at continuing the studio, the grounds and everything, to keep it going, and to continue the creative legacy that started with my parents and has continued through me and will continue after I'm gone.

It's not so much an idea of creating a museum in tribute to my parents, although their works and what they did would be embedded within it, but the idea is to continue that creative endeavor and creative spirit that the ceramic studio represents and then also incorporate the Meditation Dojo. My residence, where David and I live now, could become a residence for a visiting artist or a visiting dharma teacher. There are all kinds of ideas for the future that are exciting, mostly to preserve this place as an oasis that it's always been, an oasis for peace and calm and beauty and creativity, and just see how it could be kept as an asset right here in the middle of Jackson. We're at the embryonic stage of doing all that. We haven't quite launched out to a fundraising effort yet, but we're beginning to create the underpinning for doing that.

Bebe Wolfe was born in 1949. She grew up in an environment rich in creative potential. She is the daughter of two artists, Karl and Mildred Wolfe. She attended the Portland School of Art in Portland Maine from 1980 -1984, receiving a BFA in painting. Bebe and her husband David Weidemann moved back to Jackson in 1985 to help Bebe’s mother Mildred with the studio business. The Wolfe Studio today is a full-time business, employing many talented artists from the area. The Studio functions as a cottage industry and art collective, constantly innovating and refining our product and finding new ways to survive as conditions change around us. Bebe’s interest in Buddhism and meditation began over twenty years ago with an introduction to Zen practice. Bebe served as the facilitator for the Jackson Zen Group from 1995 to 2012 and is now helping to facilitate practice for the Jackson Insight Meditation Group. Bebe acts as host to other meditation groups that use the Dojo every week as a place of practice.

One year ago:

Mississippi Expat: Melvin Myles

"In essence, being from Mississippi has not only affected my identity and my music; it has given me a purpose. It has taught me that music can be a bridge between worlds, a healer of wounds, and a catalyst for change."

Two years ago:

Mississippi Native: Dyamone White

"Mississippi has made me a visionary. I see the state as being a blank canvas. When I travel, I see what other locations offer and think about ways to replicate those offerings in Mississippi."

Haters Gonna Hate

"As someone who thinks deeply about Mississippi history, culture, and politics on a daily basis, I get whiplash when I log on to Twitter and, out of the blue, someone who has never been here is calling for the South to 'secede already' or wondering aloud why anyone in their right mind would choose to live here."

I love what you say about "the landscape of home" - and your description of "the sparks of real creativity, of things busting out, like grass growing through the cracks in the cement." Yes! And what a beautiful story about your mother and Eudora Welty!

Another wonderful piece about this quirky place I have yet to visit, one day for sure! It's a fact that MS suffers from lack of investment and for inexplicably voting red yet scrape beneath this and it's a vibrant bubbling cauldron of artistic delights.