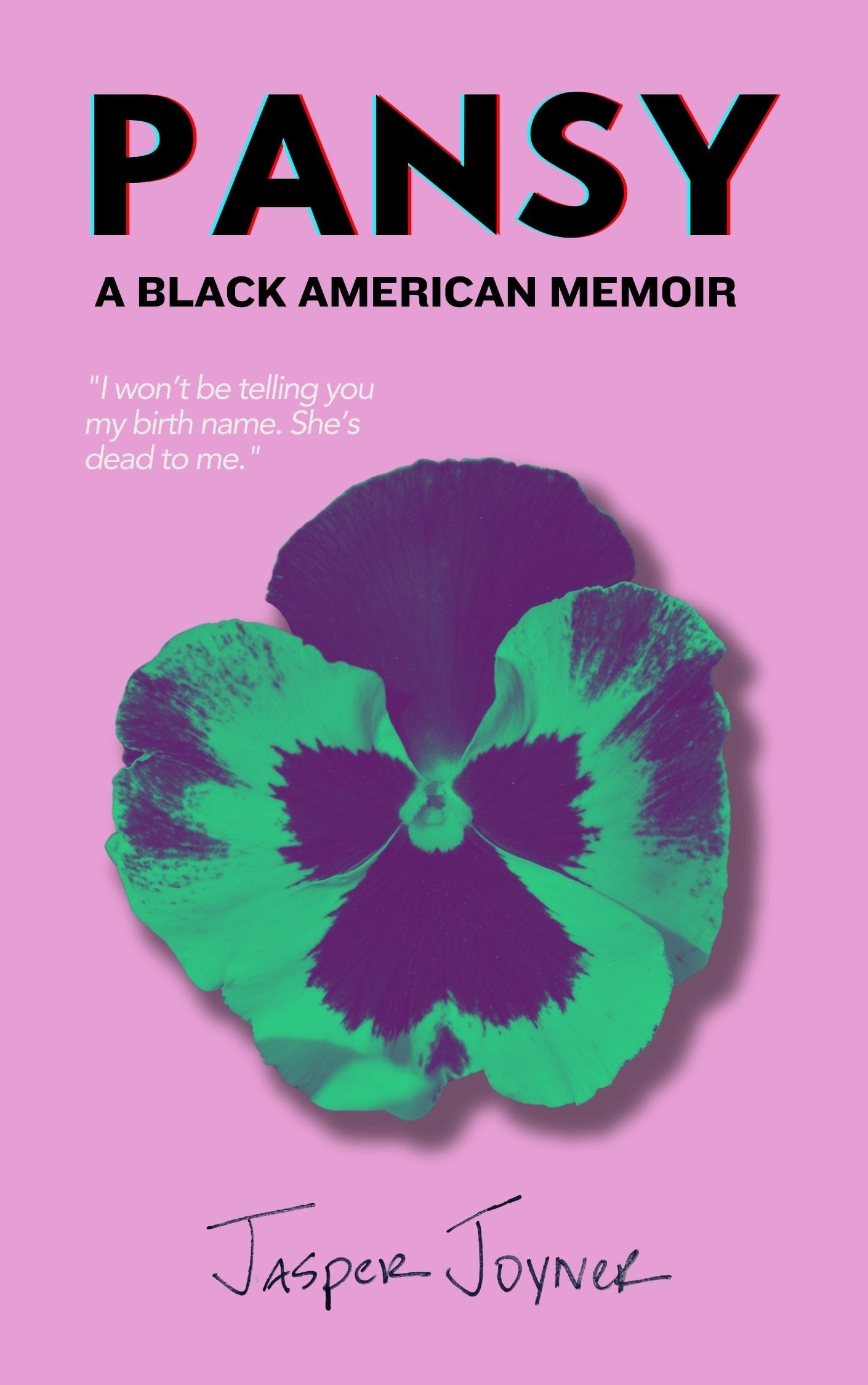

Today, we share a poem by Jasper Joyner, along with an excerpt from Pansy: A Black American Memoir, their forthcoming debut memoir. Pansy is a non-linear, episodic memoir that combines poetry, cultural criticism, and essays. It follows transmasc, southern writer Jasper as they fumble through an awkward Memphis upbringing in the 90s and early aughts, an insufferable Nashville PWI, and a fierce NYC queer awakening, all with a poignant throughline on Black exceptionalism, focused on Jasper's wildly agonizing first publishing experience with their novel, Juniper Leaves.

Let Home Be

Let home be baby wanna go home mama say stay a lil longer it’s some people I want you to meet she say some errands I want you to run food I want you to try and beautiful places and things you must see on your own now I’ll be here my sweet baby when you return I’ll be here but for now let home be in your heart let home be in your spirit let home be and I’ll stay right here right here right here just watch

Like a Kick in the Face

Memphis, TN, Fall 2005

Life, in the shape of a size-10 Doc Martens boot attached to a gaunt, pale-bodied Christian punk screamo singer atop a makeshift stage inside an indoor skatepark, kicked me in my mutherfuckin’ face.

But first, a lot of other things happened.

One of which includes my starting tenth grade at a new high school after leaving Craigmont, a place the whites of Memphis claimed was quickly “going downhill” after (Black) kids from North Memphis got bussed there.

I didn’t leave because those kids got bussed. But I cannot lie to you, other than sadly exiting my soprano spot in their epic gospel choir, or their expressly great track team, I was quite happy to hop on out that bitch because Black kids from North Memphis could see right through my charades like a camera through cellophane.

By charades, I mean the sort of scaffolding wall surrounding my jello-soft interior, of which I’d just adopted post-middle school after the harrowing realizations that I was, in fact, very, very weird. I’d accepted it. Tried for years to avoid it but there was no lying to myself anymore. Now, words like transgender or queer hadn’t blessed my vocabulary just yet, but I knew ‘gay,’ and the way it left my mouth still felt like the worst kind of slur so I rebuked it like any good Christian would. Called it ‘weird,’ instead.

My walk, like a butch robot, was ‘weird,’ not a clear sign of my dyke-itude. My sturdy cadence, though paired with a pitch sometimes only dogs could hear, did not help either. And neither did my style, of which I couldn’t possibly pretend was hitting the way it was supposed to had hit. Not at a place like Craigmont High where North Memphis girls somehow figured out a way to make a white button-up shirt and khakis look fresh. All I had to do was speak, and the Black kids at Craigmont could read me up and down like a scroll. It’s ‘cause when I spoke, I sounded like I was trying too hard.

I saw what cool was at Craigmont very fast. It was night and day different from Woodstock Middle ‘cool,’ so, none of my Woodstock cool transferred over. And I’d worked so hard for it! Still, not a bit did. And at Craigmont, it’d be foolish for me to even try. Not that I didn’t try. Nobody said I wasn’t foolish. But the mix of imitation and raw me-ness mixed up into it came out like the silliest brew of out-of-touch nerd.

One sentence out my mouth and the Craigmont kids could clock every bit of my person. They’d know my parents looked down on their parents. Could have probably predicted that just that weekend before, my Daddy had been on a rant about young Memphis thugs overtaking his band class, sounding like Uncle Ruckus. They could hear it all in my voice, all in the bend of my words that didn’t quite bend like Memphis, because they’d been expressly trained not to.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rooted Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.