Light Strike the Cave: Reading Etheridge Knight

An essay by C. T. Salazar on the life and legacy of one of Mississippi's most storied poets.

I started writing this essay out of a need to understand and demonstrate a context in which a poet like Etheridge Knight could exist. While Knight’s poetry is still relatively in print and lauded by leading scholars and poets alike, he is often cast as a figure not necessarily without history, but outside of history. I started reading Knight more deeply to better understand his brilliance and the ways it exists within a given matrix of history and social circumstances that begin and end in Mississippi. While it is common knowledge that Knight was born in Mississippi, the material genealogies and traditions of craft that arise from the state are rarely frames we use to understand Knight and his poetics.

Etheridge Knight is commonly described as a “prison poet” active from the late 1960s through the 1980s. On the back cover of his first collection—Poems from Prison—is the quote of Knight’s: “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound and narcotics resurrected me. I died in 1960 from a prison sentence and poetry brought me back to life.”[i] Thus the genesis. Not just of the poet, but the precarious social strata so many Americans find themselves in when the state prospers from the death of the dispossessed, the collateral of marginalization. Etheridge Knight came with a lyric.

Knight’s poems are widely anthologized into 20th century American poetry and Black Arts Movement anthologies. What follows below is a close reading of Knight’s poetics and an attempt to reconstruct the world Knight inhabited.

+

Nearly every social interaction in Mississippi is tinged with the touch of racial capitalism by way of incarceration. In 2021, Mississippi became the state with the second highest rate of incarceration, and the highest in 2023.[ii] So far none of our governing powers seem concerned or inspired to change course. Every institution in some not-so-distant way is affected by or has a direct relationship to the prison industry here, though most don’t confront this. As Jim Crow replaced enslaving plantations with prison systems, it’s misleading to say we’ve been losing a Black population to the prisons in Mississippi. Rather, we’ve been ensuring a Black population stays captive from the beginning.

That one of the most formidable Mississippi poets, Etheridge Knight, speaks to us from the place of a prison cell in Indiana (where he spent the beginning of his poetic career) in so many of his poems, is not an anomaly. At the rate we jail each other, it’s not a reach to believe that some of our state’s finest poets are behind bars.

That one of the most formidable Mississippi poets, Etheridge Knight, speaks to us from the place of a prison cell in Indiana (where he spent the beginning of his poetic career) in so many of his poems, is not an anomaly. At the rate we jail each other, it’s not a reach to believe that some of our state’s finest poets are behind bars. Inside World, the inmate-made newspaper of Parchman Penitentiary—the state’s maximum security facility—speaks to this. The paper ran from 1950 to the mid-1980s, with a poetry column taking up a fourth of its contents as a monthly fixture.

+

Broadside Press out of Detroit published Etheridge Knight’s first book of poems the day he was released in 1968. Those of us who have never been incarcerated have not been captives in the invisible land floating in the periphery of our society’s reality. Ruth Wilson Gilmore talks about this common view of how prisons sit on the edge—the margins of social spaces, but this apparent marginality is a trick of perspective, because “edges are also interfaces; for example, even while borders highlight the distinction between places, they also connect places into relationship with each other.”[iii] The opening poem of Poems from Prison:

CELL SONG Night Music Slanted Light strike the cave of sleep. I alone tread the red circle and twist the space with speech. Come now, etheridge, don’t be a savior; take your words and scrape the sky, shake rain on the desert, sprinkle salt on the tail of a girl, can there be anything good come out of prison [iv]

This poem is an invocation, the poet’s call to the muse. Music and light are the wellsprings of inspiration, and the speaker is summoning them forth by name. I love the concrete visual and schedule the third line creates: the start of the day is sleep, then the self, completely alone in a vast and empty margin. The muse that was called calls back. The last stanza, as implied by the punctuation, could be in the muse’s voice, but I think it’s the speaker, too, asking can there be anything / good come out of / prison.

Knight often described himself as a “poet of the belly.” In a 1986 interview with The Equinox, a student paper at Keene State College, Knight says “Ideas are not the source of poetry, it’s feelings. Sometimes the source of a poem may be an idea. For me it's passion and feeling. Then the intellect comes into play. It starts in the belly and then into the head.”

One of the many qualities to be admired in Knight’s poetry, especially his first book, is how the poet can probe these questions of cruelty and wrongness without simultaneously insinuating or reinforcing the need for prisons to exist. The catastrophes and violences that exist in Poems from Prison exist because of the existence of the prison and the conditions it demands on its occupants, and not because of the faulty idea that the people inhabiting them are innately more violent people.

+

Serving an eight-year sentence in the Indiana State Prison is where Knight started his craft, as well as correspondences with poetry luminaries Gwendolyn Brooks and Dudley Randall. Dudley Randall was the editor of Broadside Press and welcomed Knight into the fold among the Black Arts Movement among the likes of Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez. In her preface to Poems from Prison, Brooks writes:

The warmth of this poet is abruptly robust. The music that seems effortless is exquisitely carved.

Since Etheridge Knight is not your stifled artiste, there is an air in these poems.

And there is blackness, inclusive, possessed and given; freed and terrible and beautiful.[v]

Of the twenty-eight poems that make Poems from Prison, two are addressed to Gwendolyn Brooks. In the second one, directly titled “To Gwendolyn Brooks,” Knight takes on traditions of the Greek Ode and apostrophe, so as to accommodate the larger-than-life Brooks with larger than life language:

O Courier on Pegasus. O Daughter of Parnassus! O Splendid woman of the purple stitch. When beaten and blue, we despairingly sink Within obfuscating mire, Oh, cradle in your bosom us, hum your lullabies And soothe our souls with kisses of verse That stir us on to search for light. O Mother of the world. Effulgent lover of the Sun! Forever speak the truth.[vi]

So much language to cherish. The addresses dignified and harkening from the earliest moments of the Western tradition in poetry. Reading this poem, however, I can hear in Knight’s syntax the Mississippi language. Moments like beaten and blue and soothe our soul and stir us on are phrases that remind me of the language, the way of speaking I heard in my own home in rural Mississippi. This could also be because the language of the South is so quintessentially King James. Cradle in your bosom us and despairingly seem so close to language of the King James Old Testament prophets exalted into my memory, and the spiritually charged speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers.

+

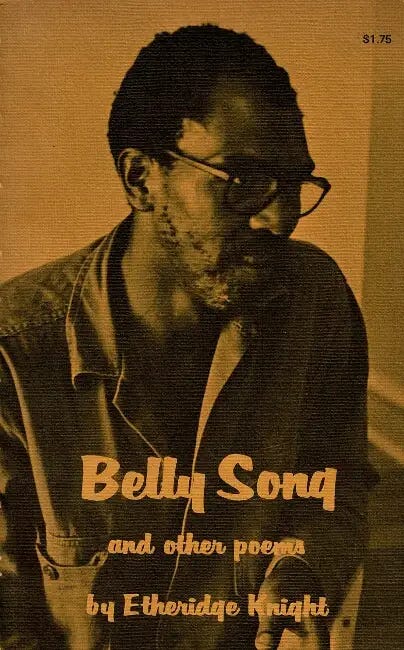

Knight’s second collection, Belly Song and Other Poems (1973) was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. All of the Pulitzer Prizes for poetry in the 1970s were awarded to white poets. Creation stories stand a better chance of being true if they begin in the belly of something. Knight often described himself as a “poet of the belly.” In a 1986 interview with The Equinox, a student paper at Keene State College, Knight says “Ideas are not the source of poetry, it’s feelings. Sometimes the source of a poem may be an idea. For me it's passion and feeling. Then the intellect comes into play. It starts in the belly and then into the head.”[vii] Ahmos Zu-Bolton, fellow Mississippi poet and veteran of the “slave ship called the U.S. Army,” describes this second collection of Knight’s in a short memorial piece published a decade after Knight’s passing in Black Magnolias:

I always thought Belly Song was, in many ways, Etheridge’s signature book. Etheridge thought he was getting out of prison, but what he found in the outside world was something so akin to prison that he went deep into his gut to produce these “belly songs” for his tribe to sing. [viii]

Zu-Bolton first found Etheridge Knight’s work in the midst of a deployment in Germany as an Army medic. Zu-Bolton’s superior officer caught him writing poems one evening, fugitively, as idle hands for an enlisted member are often a punishable offense. But the superior who had been a daily torment became human to him for the first time. Sergeant First Class Lois Knight told the medic, “My brother is a poet, he just published a book,” and the next day, a copy of Poems from Prison was in Zu-Bolton’s office mail, with the note This is a loan, please return to L.K. “The year was 1968,” writes Zu-Bolton “and it would take me over 10 years to return that book to Lois Knight.” [ix]

+

Belly Song and Other Poems was well-circulated, especially in Mississippi. In the 1970s, thanks to Jackson State University and Tougaloo College, the city of Jackson was a hub for Black poets, with a revolutionary approach to their practice. Margaret Walker landed in Jackson to teach at Jackson State in 1949 and what followed was three decades of Black poetic livelihood among a community of poets who read each other and historicized each other’s work by writing about it critically. Among this group of community-oriented poets was Jerry W. Ward Jr. (English professor at Tougaloo), Virgia Brocks-Shedd (head librarian of Tougaloo), Nayo-Barbara Watkins (Mississippi transplant by way of Freedom Summer), L.C. Dorsey (social worker and prison rights advocate), Charles Tisdale (editor of The Jackson Advocate), and Julius E. Thompson (professor of history at Jackson State University). With Margaret Walker at the center, this constellation of poets accomplished the heavy lifting of punching each other up. They became their only needed resource—creating the outlets to circulate each other’s poems, creating the workshops to learn from each other, and maintaining meaningful community spaces where Black Mississippians in Jackson could understand themselves as poets.

Here was a poet who knew love and knew anger, and knew how both could be the engine of a poem.

All of this is to say that Etheridge Knight may not have been physically in Mississippi when Belly Song and Other Poems came out, but the poets within the state were engaging with the collection critically and contextualizing it within the state’s Black literary tradition. In his seminal essay “The Black Poet in Mississippi,” Julius E. Thompson catalogs every significant collection published in the decade of the 1970s, and of 1973, Thompson says it was “a banner year, with three major collections, Belly Song and Other Poems by Etheridge Knight; Revolutionary Petunias and Other Poems by Alice Walker; and October Journey by Margaret Walker.” Thompson wasn’t wrong—three collections from poets who would continue to shape the direction of American poetry well into the 21st century were released in the same year and all three had direct ties to Mississippi.

+

Belly Song and Other Poems was the perfect second collection. The difference between Knight’s first collection and this one is the fact that Poems from Prison showed us a poet captive in an interior, while Belly Song blew up the interior until it could hold the whole of history with anger and love as competing origins. The collection’s title poem, “Belly Song” is a long, musical poem in four sections. The first section of “Belly Song” begins:

1

And I and I / must admit

that the sea in you

has sung / to the sea / in me

and I and I / must admit

that the sea in me

has fallen / in love

with the sea in you

because you have made something

out of the sea

that nearly swallowed you

And this poem

This poem

This poem / I give / to you.

This poem is a song / I sing / I sing / to you

from the bottom

of the sea

in my belly [x]The poet telling us the origin of his song. A primordial sea that belongs to a “me” and “you” but dwells in the belly. The poem itself is a gift (“I give to you”) from that sea. I used to think that while lyrical, “Belly Song” was deeply autobiographical. I understand now the error in this: autobiographical would mean the poem is explaining a “how.” Instead, “Belly Song” is an ars poetica—it explains a “why” behind Etheridge’s poem-making. The why is that through it all, Knight is carrying something inside him that’s not shrapnel. Knight had something that brought him back to life and it would turn out to be a gift he also needed to give away. The ars poetica explains not only Knight’s poem-making, but the praxis for his fundamental belief in the democratization of poetry through community-building.

+

I think of the belly as the origin of any passionate feeling. I first discovered Knight in reading the work of one of my mentors, Randall Horton. Reading Horton’s collection, Pitch Dark Anarchy, I couldn’t fathom where these poems were coming from. I had never read poems like his poems, so full of love and anger. Brimming joyously! with both. How these elements could exist not just together in a poem, but together in a line, together in a word.

Horton’s poem “III. Dear Etheridge” ends:

dear etheridge: explain to me how do i enjoy physical wonder between space & time? do you know i am leftover fragments sprawled above dark-green grass looking up a zenith float away? i have been reduced to sound, an unseen motion of alphabets. … i am sisyphus running uphill to brave the eddy in darkness, to catch hope—: to catch light. [xi]

I had a name: Etheridge. The first book I could find of Etheridge Knight’s was The University of Pittsburgh Press’s 1989 volume The Essential Etheridge Knight. An unassuming volume of 115 pages, it reorients how we think of the word essential. Reading it meant discovering the ways Randall Horton’s poetry didn’t exist in a vacuum, but extended a long conversation across generations of poets. Here was a poet who knew love and knew anger, and knew how both could be the engine of a poem. The first poem I ever read of Etheridge Knight’s was “The Idea of Ancestry,” which begins:

1 Taped to the wall of my cell are 47 pictures: 47 black faces: my father, mother, grandmothers (1 dead), grand- fathers (both dead), brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins (1st & second), nieces, and nephews. They stare across the space at me sprawling on my bunk. I know their dark eyes, they know mine. [xii]

The two-part poem begins in litany. Repetition in language will always lend itself to be something like a habit or a prayer. Most charming to me when I first read this poem was this section’s use of punctuation to foreground the idea. Commas act as tireless connectors of segments and parentheses show how things are contained together. The speaker in the cell is seeking is to be connected with his people. Yet, if the first section shows how the speaker is joined with his family, the second section disrupts that, even as the second section puts the speaker back with his family physically:

2 Each fall the graves of my grandfathers call me, the brown hills and red gullies of mississippi send out their electric messages, galvanizing my genes. Last yr / like a salmon quitting the cold ocean-leaping and bucking up his birthstream / I hitchhiked my way from LA with 16 caps in my pocket and a monkey on my back. And I almost kicked it with the kinfolks. I walked barefooted in my grandmother’s backyard / I smelled the old land and the woods / I sipped cornwhiskey from fruit jars with the men / I flirted with the women / I had a ball till the caps ran out and my habit came down. That night I looked at my grandmother and split / my guts were screaming for junk / but I was almost contented / I had almost caught up with me. [xiii]

The punctuation that enters the second part of “The Idea of Ancestry” is the forward slash, or vestibule. Forward slashes initiate a kind of violence, best summed up by the poet Natalie Diaz, who remarked on her own use of the slash in Poetry Society of America’s “In Their Own Words” series:

But in reference to the forward slashes, they aren’t meant to be exciting. I hope they make the readers’ eyes uncomfortable, that they physically and musically express the disjointed, jagged experience explored in the poem. The text within the slashes can be removed but is responsible for the fractured experience. [xiv]

In the disconnection from his family, Knight’s speaker enters a mode of regret expressed thoroughly in anger. How love and anger are inseparable. To experiment in one is to ask a question about the other.

Reginald Dwayne Betts writes remarkably on Knight’s anger as a central part of Knight’s greater poetics. In “Feeling Fucked Up: The Architecture of Anger,” Betts says:

Knight’s life was filled with angst and anguish that filtered into his poetry; the emotions manifested as a hard-edged wisdom and demonstrate how anger can be conveyed with intentionality through poetic decision, as opposed to solely as a consequence of subject. Maybe more to the point, Knight’s work demonstrates how anger can be a bridge to the poetic moment that allows the private of one life to enlarge and enliven the way a reader experiences some aspect of the world. [xv]

+

Knight’s anger cannot be discussed in a vacuum and will inevitably call for love to follow. The relationship between the two is not the usual dialectic; rather we may better understand the poetic energy behind his poems as loving-anger. This energy comes with context. Black men from Mississippi returned as veterans from wars and returned angry. Medgar Evers, Amzie Moore, Aaron Henry, and Sam Block are Mississippi’s prominent male actors of the Civil Rights movement—all four have been described by historians and biographers as charismatic and passionate, but all four described themselves as angry. They grew up as Black men in the closed society of Jim Crow Mississippi. The United States drafted them, demanding they take up arms to defend their nation’s right to segregate and lynch them. This is not to suggest that Knight should have been a Civil Rights leader, only that there exists more than one instance in which we can observe the specific transformation of the raw materials of similar lives.

Still, in Etheridge’s poems we can see a mix of material consciousness and Pan-African liberation struggle spoken plainly–much in the manner of Medgar Evers and Amzie Moore. A short unpublished poem, dated January 1969 in University of Toledo’s archive is titled “NEW MILITANT:”

I froze my feet parking cars on New Year’s Eve. The white ladies were dressed so fine. Something in me snapped. [xvi]

Another poem, titled “WINNERS” in the same archive but date unknown, ends with the final two lines: “Since the pig won’t get hip and come off his trip / we believe our freedom is worth taking!!!” [xvii]

Knight’s love poems often praise women’s bodies as fluid states of beauty, while contrasting the speaker’s own body as a fixed consequence of violence. In “The Stretching of the Belly,” a poem meditating on his partner Charlene Blackburn’s pregnancy, the poet ends the poem:

Scars are stripes of slavery Like my back Not your belly Which / is bright And bringing forth Making / music. [xviii]

The poet’s I is a collective I embodying the violence enacted on Black men in the south across time and space. This use of the poetic I as a long embodiment of loving-anger can be observed as a rhetorical gesture common in the poetics of Black Mississippians. Knight’s contemporary, Margaret Walker, begins the poem “Since 1619” with “How many years since 1619 have I been singing spirituals? / How long have I been hated and hating? / How long have I been living in hell for heaven?”[xix]

Knight’s orientation of gender and the relationship to beauty is not just something he applied to bodies and subjects in his poems, but also in his understanding of language and its utilities. Late into his career, Knight published a lecture in a 1988 issue of The Black Scholar titled “On the Oral Nature of Poetry.” In the lecture, Knight notes that words don’t exist in a static state, but instead language works for its ability to be tooled in various ways that could be understood as gendered. “There are no two sides to a word” Knight says, but “What I call the masculine, lineal side: the authority for that side of the words comes out of Webster’s or the Oxford dictionary. On the connotative side, the feminine side, the authority comes from common agreement. That’s the side of language where nuance and inflection come in; we have to agree that the authority is inside, not outside, us.”[xx] This gendered difference in Knight’s thinking is baffling. Knight is an overtly masculine presence, but his relationship to ‘authoritative,’ ‘lineal’ and therefore masculine language seems to be in contention to his interests as community-minded poet. Knight never declares that a people’s language is inherently feminine, but he’s describing a cooperative, democratic language practice as feminine, and the “gender” of language he seemed to prefer inhabiting.

An early reader of this essay wants to know why I haven’t acknowledged Knight’s failed marriages, called-off engagements, and lifetime of uninhibited drug abuse. Maybe I’m avoiding telling you the biography of a failed and haunted man. Maybe I haven’t brought it up until now out of frustration for how scholars often favor these biographical facts instead of applying a critical reading to Knight’s work.

Maybe the difficulty of describing loving-anger is attempting to institutionalize for predominately white audiences what lives as a Black art. This act flattens what is a multi-dimensional episteme connecting geographies of time and space into something as legible as a thesis. In an interview with Sanford Pinsker for the African American Review some of these difficulties of legibility come into conversation:

Sanford Pinsker: And what about other analogies—say to the matter of rage or shrillness or whatever? Are today’s women poets like the loudest, most insistent voices one remembers from the ‘60s?

Etheridge Knight: That’s something else, I think. For instance, Baraka is labeled as a “protest poet.” They say he wrote hate poetry. But that’s bullshit because all art, especially poetry, is ultimately about love. The motivating force, the creative impulse, has to be out of love. There’s no such thing as “hate poetry” because that’s a contradiction in terms. Poetry is ultimately celebratory, ultimately healing—or else it ain’t art. Beyond the blues, beyond lamentation, beyond woe-is-me, there’s always the sun gonna shine in my back door someday.[xxi]

+

An early reader of this essay wants to know why I haven’t acknowledged Knight’s failed marriages, called-off engagements, and lifetime of uninhibited drug abuse. Maybe I’m avoiding telling you the biography of a failed and haunted man. Maybe I haven’t brought it up until now out of frustration for how scholars often favor these biographical facts instead of applying a critical reading to Knight’s work. The biographical framing I’m attempting to understand his work though is as follows: He was born in Corinth, Mississippi in 1931. He dropped out of high school and enlisted in the Korean War. A shrapnel wound left him with lifelong disability, though we do not know the extent. Convicted of robbery in 1960 and sentenced to prison. Began writing poems. Lived in various states, returning to Mississippi periodically. Married Sonia Sanchez. Married Mary McAnally. Married Charlene Blackburn. Ongoing drug addiction is often cited as the reason for divorce. Published three collections of poems and edited one anthology. Nominated for the National Book Award and Pulitzer. Awarded a National Endowment of the Arts grant in 1972 and a Guggenheim fellowship in 1974. Taught at University of Pittsburgh, University of Hartford, and Lincoln University. Facilitated “Free Peoples’ Poetry Workshops” in bars in every city he resided in, either as a housed or unhoused resident. In 1990 he earned a BA in American poetry and criminal justice from Martin Center University. He died of lung cancer in 1991.[xxii]

I see the contradiction in myself at work. Frustration over how little we read Knight as a poet than as a biographical spectacle is leading me to unpack Knight’s biography and historical positionality to read him better—to know there’s a way to take in the full man without flattening the brilliance of his art. This is in stark contrast to my education and vocation as an archivist, where we understand the existence of a life and the existence of all the artifacts it makes as two separate lives entirely. We become historians when we use one to explain the other, but all we’re doing in that act is creating yet another separate life—one we have the comfort in explaining from conception to death. Etheridge Knight’s complexity in some ways invites us as individuals to reckon with these contradictions. Contradictions Knight may or may not have understood as genders. Rhetorical acts that have different aims and answer to different modes of governance but nevertheless touch each other.

Maybe somewhat describing himself and his place in the order of things, Knight writes in the preface to his third collection, Born of a Woman (1980):

Poets are naturally meddlers. They meddle in other people’s lives and they meddle in their own…Some poets meddle for a lloongg time, till their hair is white, like Robert Frost; and some poets meddle only for a moment, like Henry Dumas, shot in the back at twenty-four by one of “New York City’s Finest” in a subway station. Some poets meddle big, like Mao, who sang his song to hundreds of millions, and some poets meddle little, like Emily Dickinson, tucking her poems among the cookies that she shared with neighbors. All poets meddle, in one way or another.[xxiii]

How did Etheridge Knight view his own practice of “meddling?” In “Trouble Over” Knight’s colleague Ellen Slack says:

This man is not always easy to know; that is to say he can be difficult. He has a certain ability to, as he says, ‘stir things up.’ When the stirring starts, look out for crossfire and beware of shrapnel. Remember that you are dealing with someone who has known shrapnel which is not figurative. Some people clash violently with him; others find him threatening and make themselves scarce.[xxiv]

Not easy to know. Christopher Gilbert describes the white middle-class poetry audience of the 1980s which Knight often found himself in front of, and the “immeasurable gulf” that always existed between Knight and his audience—how even out of prison he still found himself in a kind of isolation.[xxv] An incarceration he could never escape so long as he existed in context to the greater order of things. In “Hearing Etheridge Knight,” Robert Bly says “I believe that Wallace Stevens and Etheridge Knight stand as two poles of North American poetry.”[xxvi] I’m sure the implications of this binary are complex, but the first thing that strikes me is that a biographical background of Stevens is never deemed necessary to read his critically-acclaimed poems. Michael Collins, author of Understanding Etheridge Knight draws attention to Bly’s parallel, stating “If one accepts Bly’s claim that Knight at his best is as strong a poet as Wallace Stevens… then Knight’s writing demonstrates that there is no need to choose between aesthetic achievement and political engagement.”[xxvii] Poets of a certain class get to exist without the mess of context and the trouble of history. This is not to say Wallace Stevens wasn’t a political poet (what’s an apolitical poet?), but that Knight’s poetics is grounded in a peoples’ participation, messy with democratic transmission.

+

Sanford Pinsker: And yet without the conviction that one’s language is alive, vibrant, I suspect one also can’t be a poet. So where does that leave the poet with regard to his language?

Etheridge Knight: I don’t know any other language, so I know what I’m going to say is biased, but this American language is a bitch. [xxviii]

+

For every account of Knight being hard to get along with, angry, or belligerent, there is a deeper account of him being loving and compassionate. To understand him as a force of anger is to not understand him at all. When describing his own poetics, he often says it begins in the belly as a point of origin, but formally, Knight describes his work as informed by his own people—that he chooses to rhyme because if “you asked a Black man on the street what a poem is, he’d say it’s a thing that rhymes.” Part of Knight’s ambition as a people’s poet and a community arts activist was to create a space for Black men to participate in an ongoing poetic experiment. “A Leap is made, A Dance begins, the Art happens” writes Knight in an undated lecture note archived by Butler University, “a Communication exists between the poet, the poem, and the people.”[xxix]

When describing his own poetics, he often says it begins in the belly as a point of origin, but formally, Knight describes his work as informed by his own people—that he chooses to rhyme because if “you asked a Black man on the street what a poem is, he’d say it’s a thing that rhymes.”

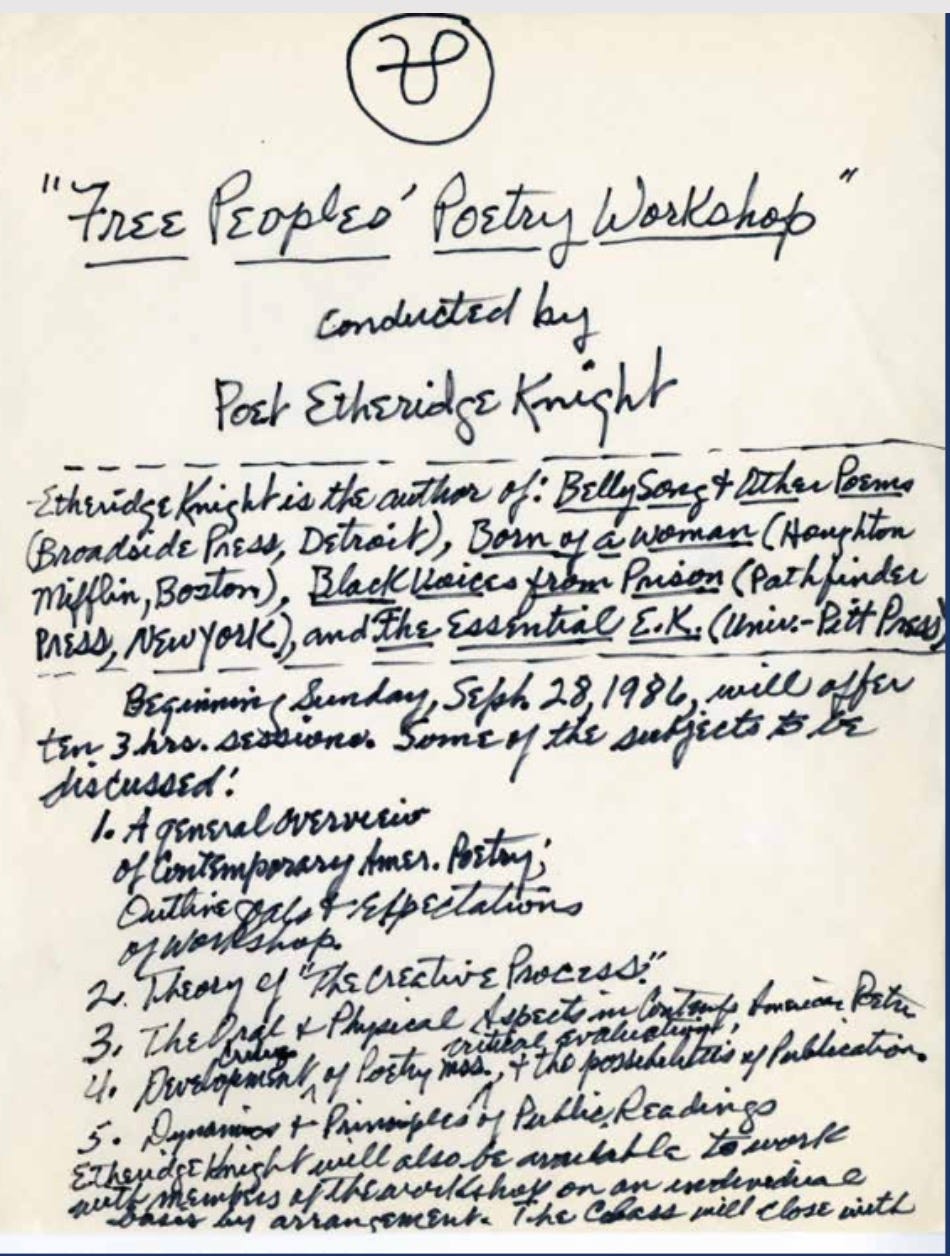

Knight’s love for community can be readily seen in both his discipline and generosity in facilitating the Free Peoples’ Poetry Workshops and how massive they were in scope. A hand-drawn flyer advertising the workshop reads, “Beginning Sunday, Sept. 28, 1986, will offer ten 3 hrs. Sessions.” By 1986, Etheridge Knight is the author of three poetry collections, winner of Guggenheim and NEA fellowships, and is advertising thirty hours of his time and attention at no cost to the community. “Some of the subjects to be discussed,” lists the flyer:

1. A general overview of Contemporary Amer. Poetry: Outline goals + expectations of workshop 2. Theory of “The Creative Process.” 3. The Oral + Physical Aspects of Contemp American Poetry 4. Development critique of Poetry mss., critical evaluation, + the possibilities of publication. 5. Dynamics + Principles of Public Readings Etheridge Knight will also be available to work with members of the workshop on an individual basis by arrangements.[xxx]

One of the ways Knight’s loving-anger manifests among community is how the anger in Knight’s poems is often a meeting space where audience can share the recognition of experience; how this place-making is quintessentially an act of love. Reginald Dwayne Betts recalls an anecdote Eleanor Wilner told him about Knight’s poem “Feeling Fucked Up,” a poem readily agreed on to be one of the angriest, rawest poems in American poetry:

Wilner told me of a poetry reading at a women’s prison where Etheridge read his poem “Feeling Fucked Up.” And then was asked to read it again. And then was asked to read it again, and again until he’d read the poem ten times.[xxxi]

“Feeling Fucked Up” crosses a threshold most poets aren’t willing to cross. The agony of heartbreak is often read from a distance, for too close up the emotion loses its aesthetic safety. Knight abandons the aesthetic for a poem that must be screamed to be read properly, in which every ounce of anger is directed at the speaker. In this act, the poem triggers the “I” of every audience member who witnesses the poet-performer act out the “anger” stage of grief:

fuck Coltrane and music and clouds drifting in the sky fuck the sea and trees and the sky and birds and alligators and all the animals that roam the earth fuck marx and mao fuck fidel and nkrumah and democracy and communism fuck smack and pot and red ripe tomatoes fuck joseph fuck mary fuck god jesus and all the disciples fuck fanon nixon and malcolm fuck the revolution fuck freedom fuck the whole muthafucking thing all i want now is my woman back so my soul can sing [xxxii]

+

Looking at Etheridge’s career spanning three collections and the few hundred unpublished poems from his archives (many of which have now been printed for the first time in The Lost Etheridge edited by Norman Minnick, 2022), one can see he favored a folk tradition of poetics. The forms that dominate Knight’s body of work are the toast, the blues line, and the Black (or jazz) haiku. It’s not common to catch the toast as a form in our contemporary American poetics, but Joseph Bruchac reminds us of the toast’s traditional function as “an oral form of poetry once extremely common in prisons. They are long, rhymed poems which speak of such Trickster figures and heroes from black culture.”[xxxiii] Is “Belly Song” a toast? Among the pages of Belly Song this description is fitting as a form. “A Poem To Be Recited” begins:

A poem to be recited while waiting in line to sign / up for your unemployment check or while standing in line to be fed in the prison mess-hall or while boarding a troop / ship for Vietnam or while walking thru the playground in “the projects:” [xxxiv]

The toast on the page carries the artifact of its origin now embedded and signified by the redundancy print has developed. On the page, all of the above is the first stanza, even though the syntax and that colon tell you the poem is about to begin. Even with all this context, is Etheridge Knight a poet always one frame away from his own context? Read aloud and following the gesture of the colon at the end of the first stanza, the poem begins:

The children of Blk america grow up quickly (and they die young. The children of Blk america grow up quickly (and they die young. [xxxv]

Think about existence as dying in the fourth line—in a double-opened parenthesis. A child dies when they go to war, and dies again when the only suitable home the state can provide upon their return is a prison. A parenthesis inside another parenthesis; the prison within the prison where Black captives live in the heart of America. “His poetry comes from the prison subculture,” writes Bruchac, “and then goes beyond it—if it is possible to talk about going beyond something which is not left behind.”[xxxvi]

The toast as a poetic mode doesn’t often leave prison grounds. To be a master of the toast is to be witty, intelligent, and good with words in such a way that can entertain groups of incarcerated men. They’re memorized; they’re scratched into walls by anonymous authors and added on to by collaborators; it’s a form of currency to entertain yourself and create theater for your fellow captive community. It’s a deeply communal form and in this way, the toast is bound by space and time. Maybe because of this, Knight’s poetic mode wasn’t easily legible to the poets outside this community. To be a poet of both “academies” was to belong fully to neither. In a letter to Amiri Baraka, digitized by the archives of Butler University in Indianapolis, Knight makes a case for his use of the toast, writing, “I don’t know if my book will be ‘literary,’ — all I know is I’m taking back the Authority of our Oral Tradition that’s been mainly stolen/exploited by white boy ‘folklorists,’”[xxxvii] For Knight then, reclaiming the toast was a democratic act of seizing representation to an art he had right to, where it had previously been commodified and extracted outside of his community.

Etheridge Knight was a poet of the belly. Deeply Mississippian in his troubles, which is deep in the belly of the contemporary American death machine that looked unique in its presentation of a prison, but his own vision and practice rooted the fact that it was still just a plantation.

While many of the Black poets in Mississippi in the first decades of the 1900s who made a point to write poems in a Western sense as a mode of art wholly separate from another popular Black poetic tradition—blues music—Etheridge Knight’s poetry often unified or reclaimed the blues as a poetic mode. Knight’s somewhat unique positionality as poet given credibility early on in his career by Gwendolyn Brooks, Sonia Sanchez, and Amiri Baraka, coupled with the material circumstances of Knight’s life made him the perfect transmitter for blues as a poetic mode to re-enter Black artistic expression as late as the 1970s and 1980s Black Arts Movement. An example of this can be found in the succinct poem “Sharecropping Economics 101,” unpublished in Knight’s lifetime but appearing in Minnick’s The Lost Etheridge:

Our father who / up / in Heaven: White man owed me ‘leven, but pay / me / seven. Thy Kingdom come, Thy Will be done: But if I hadn’t took that, I wouldn’t got none! [xxxviii]

Knight’s most iconic poem “Feeling Fucked Up” shares subject with the blues tradition–the wailing that comes with the ending of a relationship. With the opening line “Lord she’s gone done left me done packed / up and split”[xxxix] could be the opening line to a song from Albert King, Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt or any other male blues songwriter.

+

Sanford Pinsker: Maybe this is a good place to make you come clean about how much poetry, especially traditional poetry, you know—despite everything you’ve said about an oral tradition and the obvious truth in it. Gerald Stern used to claim you were a closet reader, somebody who knew more poetry than you let on. Is he right?

Etheridge Knight: Well, I can tell you this: I understand that Carl Sandburg is supposed to be on the outs with academics, but I know exactly what he was talking about. And I know I was not his primary audience. But that doesn’t stop me from getting into his poetry. I can get into Robert Burns. I can get into Shakespeare, and I know damn well Shakespeare wasn’t addressing me. I was nowhere near his imagination.[xl]

+

While I’ve been wanting to think through an inward conversation about Knight’s poetry fully contained within the socio-cultural bounds of Mississippi, I also want to acknowledge the farce of these drawn lines. If Mississippi is a landscape of physical, spiritual, economical, psychological, and historical tangled strata it is never actually contained within its own idea of statehood, especially as it is transmitted through its people. Knight “came out of the Southern tradition and consequently, he remained in the Southern tradition, even when he was elsewhere” says poet Yusef Komunyakaa.[xli] Knight’s ongoing “elsewhere” means he’s part of an anthropological phenomena linking Mississippi’s geography inseparably to everywhere else. One can draw many other traditions Knight participates in, but I’m especially curious in how Knight writes to us from a globally incarcerated planet. Imagining all the peoples of every culture, time, and place oppressed and rendered less-than-human through imprisonment makes a reading between Etheridge Knight and another poet like St. John of the Cross a generative dialogue. While I don’t have the space here to explicate, I do want to question: if we read the 16th century Spanish mystic poet as a poet who in fact wrote his canonized poems while incarcerated, what can we see in the conversation between St. John’s poem “Dark Night” (“Noche Oscura”) and Knight’s poems? The final stanza of “Noche Oscura” as translated by Willis Barnstone:

I lay. Forgot my being, and on my love I leaned my face. All ceased. I left my being, leaving my cares to fade among the lilies far away. [xlii]

In an era in which geographers are starting to map the “place” of prisons, a 20th century Mississippi poet and a 16th century Spanish poet can show us how not so distant the lands really are. Between Knight and St. John, a scholar could further articulate how part of our prison problem—at least spatially—is paradoxically a problem of immeasurable distance and impossible proximity.

+

Etheridge Knight was a poet of the belly. Deeply Mississippian in his troubles, which is deep in the belly of the contemporary American death machine that looked unique in its presentation of a prison, but his own vision and practice rooted the fact that it was still just a plantation. It could be undone with songs transmitted fugitively and it could be wracked with insurgent liberation. Knight himself would spend his entire life clawing for that liberation. Knight’s poems were spoken and audiences found themselves in the torrent of his loving-anger. When Knight read at the Library of Congress in 1986, Gwendolyn Brooks introduced him. Before Knight took the podium, Brooks spoke, “His vision is merciless. He spares himself nothing, and he spares you nothing…Many, many visions visited your cell, Etheridge Knight, and they educated you. They vaulted you. Come here and open your mouth.” [xliii]

+

Genesis the skin of my poems May be green, yes, and sometimes wrinkled or worn the snake shape of my song may cause the heel of Adam & Eve to bleed . . . split my skin with the rock of love old as the rock of Moses my poems love you [xliv]

C.T. Salazar is a Latinx poet and librarian from Mississippi. His debut collection Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking (Acre Books 2024) was a 2023 finalist for the Theodore Roethke Memorial Award. His most recent poems have appeared in Poem-A-Day, Poetry Northwest, Denver Quarterly Review, Cincinnati Review, West Branch and elsewhere. C.T. is an assistant professor at Delta State University where he directs the University Archives and Museums.

[i] Etheridge Knight, Poems From Prison (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1968).

[ii] Jerry Mitchell, “’Foolishly sticking with failed system’: Mississippi lead the world in mass incarceration,” The Clarion Ledger, August 13, 2022, https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2022/08/13/mississippi-has-more-inmates-per-capita-than-any-state-nation/10317601002/

[iii] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California (Berkley: University of California Press, 2007).

[iv] Knight, 2.

[v] Knight, back cover.

[vi] Knight, 11

[vii] Colleen Cowette, “Toast teller turned to poet writes on prison life” The Equinox February 19, 1986. https://www.ekfreepeoplesbe.com/toast-teller-turned-to-poet

[viii] Ahmos Zu-Bolton, “Etheridge Knight: A Memoir,” Black Magnolias Volume 1, No. 1 (2002), 14-18, http://www.psychedelicliterature.com/blackmagnolias.html

[ix] Zu-Bolton, “Etheridge Knight,” 14.

[x] Etheridge Knight, Belly Song and Other Poems (Detroit, Broadside Press, 1973).

[xi] Randall Horton, Pitch Dark Anarchy (Chicago: TriQuarterly Books, 2013).

[xii] Etheridge Knight, The Essential Etheridge Knight (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986).

[xiii] Knight, 13.

[xiv] Natalie Diaz, “Natalie Diaz’s ‘Hand-Me-Down Halloween,’” Poetry Society of America, https://poetrysociety.org/poems-essays/in-their-own-words/natalie-diaz-on-hand-me-down-halloween

[xv] Reginald Dwayne Betts, “Feeling Fucked Up: The architecture of anger,” The American Poetry Review, volume 41, No. 3, https://aprweb.org/poems/feeling-fucked-up-the-architecture-of-anger

[xvi] Etheridge Knight, (January 1969) Etheridge Knight Papers, Ward M. Canaday Center Archives, University of Toledo.

[xvii] Knight, Etheridge Knight Papers.

[xviii] Knight, The Essential Etheridge Knight, 29.

[xix] Margaret Walker, This Is My Century: New and Collected Poems (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013).

[xx] Etheridge Knight, “On the Oral Nature of Poetry,” The Black Scholar, 19.4, 1988, 92-95.

[xxi] Sanford Pinsker, “A Conversation With Etheridge Knight,” African American Review 50.4 2017.

[xxii] Catharine S. Brosman, “Etheridge Knight,” Mississippi Poets: A literary guide, (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2020).

[xxiii] Etheridge Knight, Born of a Woman: New and Selected Poems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980) xiii

[xxiv] Ellen Slack, “Trouble Over,” Painted Bride Quarterly, Number 32/33 1988, 23-25.

[xxv] Christopher Gilbert, “The Breathing/ In/ An Emancipatory Space,” Painted Bride Quarterly, 32/33 1988, 117-134.

[xxvi] Robert Bly, “Hearing Etheridge Knight,” Painted Bride Quarterly 32/33, 31-35.

[xxvii] Michael S. Collins, Understanding Etheridge Knight (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012).

[xxviii] Sanford Pinsker, “A Conversation With Etheridge Knight,” African American Review 50.4 2017, 711-714.

[xxix] Etheridge Knight, Belly Dance, Butler University, “Etheridge Knight Free Peoples Be” https://www.ekfreepeoplesbe.com/transcripton-of-belly-dance-2

[xxx] Etheridge Knight, Free Peoples’ Poetry Workshop Flyer, Butler University, https://www.ekfreepeoplesbe.com/transcrption-of-free-peoples-flier

[xxxi] Reginald Dwayne Betts, “Feeling Fucked Up: the architecture of anger.”

[xxxii] Knight, The Essential Etheridge Knight, 29.

[xxxiii] Joseph Bruchac, “Seeing Through Walls: Etheridge Knight and American prison poetry,” Painted Bride Quarterly, 32/33 1988, 45-47.

[xxxiv] Etheridge Knight, Belly Song and other poems (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1973).

[xxxv] Knight, 26.

[xxxvi] Bruchac, 713.

[xxxvii] Etheridge Knight, Letter to Amiri Baraka—1984, Butler University, “Etheridge Knight Free Peoples Be” community project. https://www.ekfreepeoplesbe.com/letter-to-amiri-baraka

[xxxviii] Etheridge Knight, The Lost Etheridge: uncollected poems of Etheridge Knight edited by Norman Minnick, (Athens, Kinchafoonee Creek Press, 2022).

[xxxix] Knight, The Essential Etheridge Knight 34.

[xl] Pinsker, 714.

[xli] Yusef Komunyakaa, Blue Notes: Essays, Interviews, and Commentaries, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

[xlii] St. John of the Cross, The Poems of St. John of the Cross translated by Willis Barnstone, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972).

[xliii] Gwendolyn Brooks, “Introduction to Etheridge Knight at the Library of Congress” 1986, reprinted in Painted Bride Quarterly 32/33 1988, 9.

[xliv] Knight, The Essential Etheridge Knight.

This hits home in more ways than one. WOW

What a superb, insightful, and touching essay....thanks to CT, the Rooted Team and esp the super poets featured in this gorgeous work...Dwaine Rieves