Welcome to the Halloween spin-off edition of Mississippi Sideboard, a monthly collaboration with the food, culture, and history writer Jesse Yancy. Jesse’s long-running blog of the same name is a foray into the particularities of southern cuisine and an exploration of the lesser-known parts of Mississippi history. Today’s spooky story, accompanied by original artwork from Guillermo Salinas and Jason Jenkins, may send a shiver down your spine and cause you to approach your bottle trees with a little more caution.

Joyce Sexton was proud of her garden. It occupied the edges of her back yard along the fences—broad beds of perennials punctuated by flowering shrubs whose Latin names she had memorized because they sounded like an incantation as she recited them in her mind.

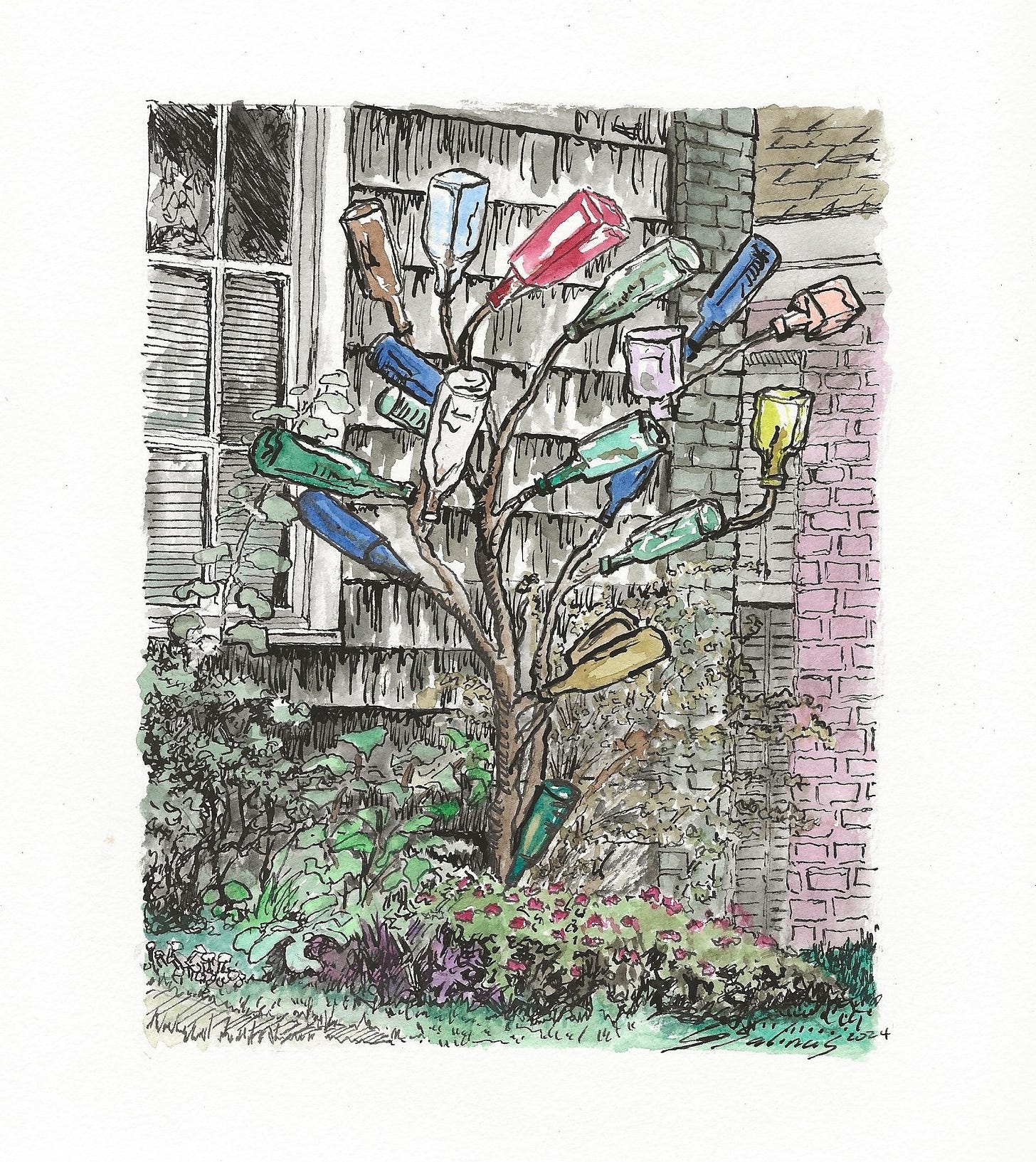

In the southwest corner was a short dead spruce stripped of twigs and leaves whose trimmed branches were adorned with brightly-colored glass bottles. Joyce enjoyed the way the glass caught the morning sun and reflected in the lights from the porch during the evenings. It had taken her months to find just the right bottles for the tree, and this morning she finally found the last one, a bright red bottle on top that seemed to glow from inside. She was admiring its light when she heard the front doorbell. She had invited her friend Sandra over for a drink.

“Well, it is pretty,” Sandra said later as they sat under the porch fans. “At least you’ve got different bottles. I don’t like those with just one kind, especially those Milk of Magnesia models. They just send out the wrong signal, if you ask me.”

“I think it’s the best bottle tree in town,” Joyce said. “I know it sounds silly, but a bottle had to really say something to me before I put it on.”

Sandra just stared at it with her arms crossed.

“You don’t like it?” Joyce said.

“Oh, like I said, it’s pretty, Joyce. And it looks good right next to the Lady Banks. But do you realize what those things are?’

Joyce laughed and said, “You mean that nonsense about trapping evil spirits? Cassandra June, your ass hits a pew every time First Pres is open. And besides, you’re over-educated to boot. Surely you don’t believe that voodoo junk. ”

Sandra sipped her gin and tonic and smiled at her old friend. “Oh, you wouldn’t care if I were sacrificing stray cats in my basement, you’d still never get along without me.”

“If you were sacrificing stray cats, I’d bring you a few,” Joyce said. “They kill the little birds, they yowl all night long and they beat up on poor Lucky.” A little terrier of dubious parentage lying under the table between them raised his head and thumped his raggedy tail.

“Okay, if you think it’s all stuff and nonsense, let me break one,” Sandra said. “Oh, don’t look so shocked. Admit you had fun looking for these bottles, and one of them’s bound to break sooner or later.”

Joyce thought about it. “Okay, you old witch,” she said. “But break one of the bottom ones. Use Glen’s putter. It’s over there on the corner.”

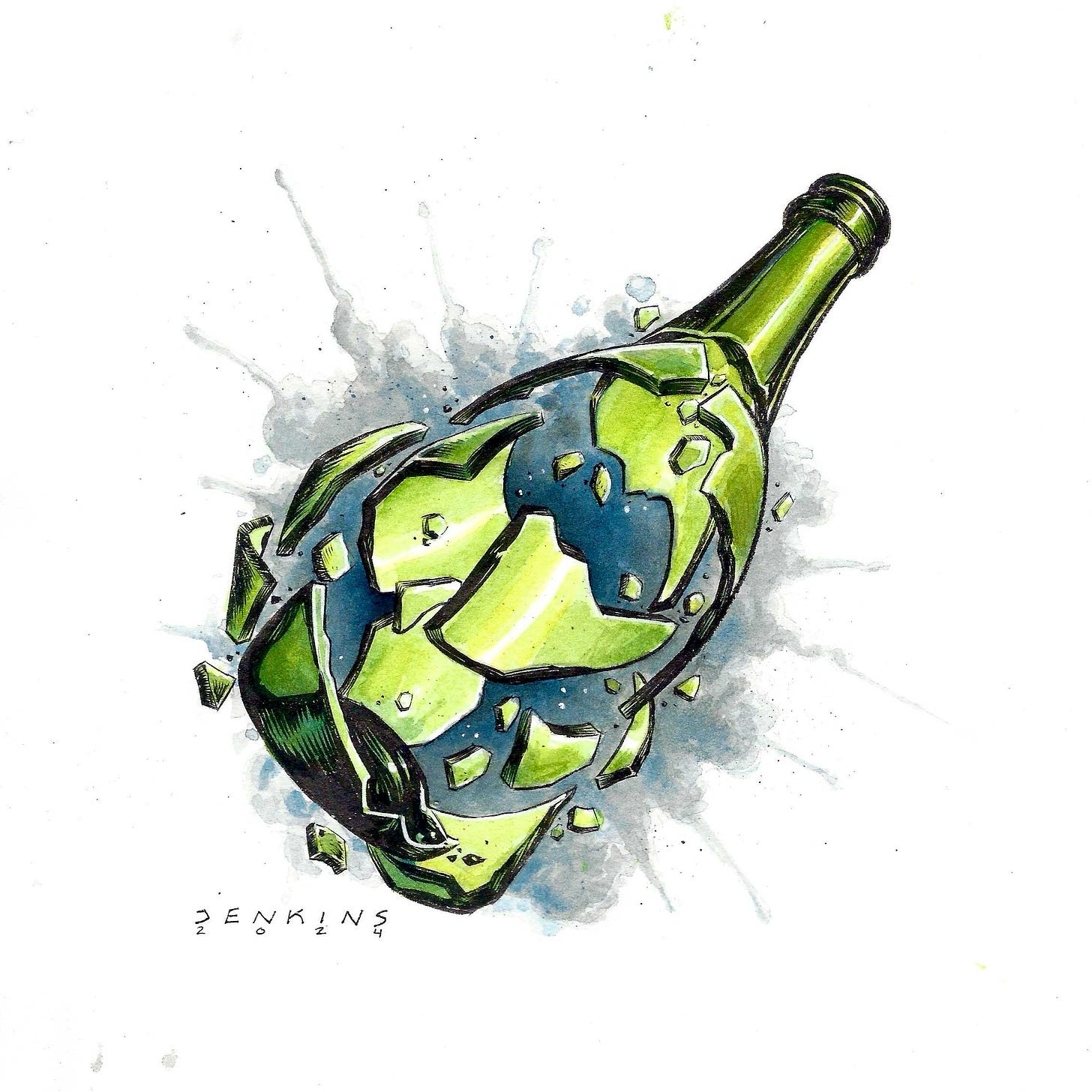

Sandra retrieved the putter, walked into the back yard and shattered a small green bottle on a lower branch. At the sound, Lucky jumped up and scrambled under the gate into the lawn outside. Before Joyce could gather the breath to summon her dog, she heard the screech of brakes and a choked, mournful howl.

“Mother, it was just an accident,” Rachel said. “Sandra shouldn’t blame herself. That’s just silly.”

Joyce looked at her daughter. She and Glen had been surprised when her infant golden hair had not only remained gold, but had also matured into a mane that Rachel merely pretended to complain about. Today she had wrestled it back into a tawny mass that spilled like a shower over the back of her bright blue scrubs.

“I know,” she said. “But you know how Sandra loved Lucky. She brought him liver snaps every time she came over. I think she did it on purpose; they always gave him gas.”

Rachel brought her coffee to the table and sat next to her mother. “Mom, just ride it out. I know you loved Lucky, too. Hell, we all did. Except Richard, of course.”

They both made a face at each other and laughed. “Cliff Stevens told me he was still wearing an ankle bracelet in Chattanooga,” Rachel said.

Joyce sipped from her cup and wished Richard were much further away. She still ran into his parents at parties, his father formal, his mother always managing to snag Joyce away from the crowd and update his doleful story. (“He didn’t mean anything, Joyce. You know that.”)

Rachel glanced at her watch. “I’ve got to go, Mom. Joe Wright told me I could scrub in on a valve replacement this morning.”

Joyce kissed her daughter and took her coffee to the patio. She called Glen at his office, forgot he was in court that day and ended up talking to his secretary Cathy about the upcoming office party.

“Glen’s just a mess about it,” Cathy said. “And I do mean a mess. He can’t decide on a damn thing, and that puts me in charge of everything from food to felonies. Would you please try to sit him down for five minutes and nail something down for me?”

“Oh, just do what you did last year, Cathy. It’s not like he’s going to notice.”

“I know,” Cathy said. “He’s such an airhead.”

Joyce laughed and said goodbye, went and poured another cup and settled back on the porch to admire her garden. The azaleas had exhausted themselves long ago, and the Shastas were now coming into their own, as were the hostas she’d planted last October. Lucky’s little grave by the native holly was marked with a shaggy little stone dog and a tossed scattering of weathered liver snaps.

The bottle tree glistened in the morning sun. One bottle caught the light extremely well, a beer bottle Joyce found behind the back fence that had a white and blue label. The light it caught dazzled.

Joyce laughed, picked a hand spade from her garden shelf, walked up to the tree and shattered the bottle into hundreds of pieces.

She was still smiling when she heard the phone ring.

“Joyce?”

Glen knocked gently at the barely open door. Joyce lay on the bed, the golden afternoon light pouring onto the floor and casting shadows upon morning windows.

“Joyce?”

He moved into the room and sat on the edge of the bed.

“Honey?”

“How did Richard get out?”

Glen turned, bowed and rubbed his hands together. “He’s been out.”

Joyce rolled over and looked at her husband’s back.

“It’s been eight years, Joyce. He was convicted as a juvenile. It was not a capital offense. He served five years, and then they put him in a rehabilitation unit. He was clean and sober; he had a job at a Walgreens. He was evaluated twice a month.”

“He just killed our daughter,” Joyce said.

Glen’s shoulders heaved and he began to sob. Joyce reached up and brought him to her and they lay there, crying, while the shadows grew on the wall.

The summer office party was never conducted, but as the holidays approached, Glen suggested that the traditional year’s end celebration be held, and to his relief Joyce agreed. The firm had had a very good year, and Glen, as senior partner, always enjoyed giving out bonuses and promotions.

Predictably, it began on a muted note, but as the night progressed, the mood lifted and Joyce found herself enjoying being around friends. As they were driving home, she and Glen found themselves laughing about Cathy’s QVC jewelry and Jerry Wineman’s new toupee.

It was warm for a winter’s evening; wisps of fog were settling into the low places along the road, and the lights from the house glowed as they pulled into their drive.

Glen grabbed Joyce’s hand and said, “Let’s sit out on the back porch and have another drink.”

“No, Glen,” Joyce said, caressing his hand, “I’d rather not. Let’s just sit in the living room.”

Glen looked at her and said, “You used to love the porch. You used to love looking at the garden. What’s the matter?”

Then Joyce told him about the bottle tree, about Lucky, about Rachel. Glen sighed and said, “Oh, honey, you know that’s just ridiculous. What did they call it in college, synchronicity? Come on, let’s build a little fire in the fireplace and huddle up next to it on a blanket with a couple of beers.”

“I’d rather have a martini,” Joyce said, smiling.

After they’d changed, Glen settled Joyce in front of the fire with her drink.

“Glen. I know it’s just a bunch of nonsense. Coincidences, like you said.”

“Of course they were, and I know it, but I don’t believe you believe it.”

“I do,” Joyce said, “And I’ll prove it to you. Is your 12-gauge in the hall closet?

“Sure.”

Joyce retrieved the gun from the closet along with a box of shells. “Show me how to load it again.” Once the gun was loaded, Joyce slung it over her shoulder and headed out the back door.”

“If you stand back about ten yards, you ought to be able to get all of ‘em,” Glen shouted. He smiled, took off his shirt and sipped his beer. Then, with a smile, he slicked back his hair and lay down on the couch. A shot echoed from the backyard.

When Joyce came running back in, she said, “Glen, I got them all! And the trunk is in splinters. I’ll have a hell of a time cleaning up all the glass. Glen? GLEN!”

Nice. And as a transplanted Mississippian, I have a bottle tree in my front yard.